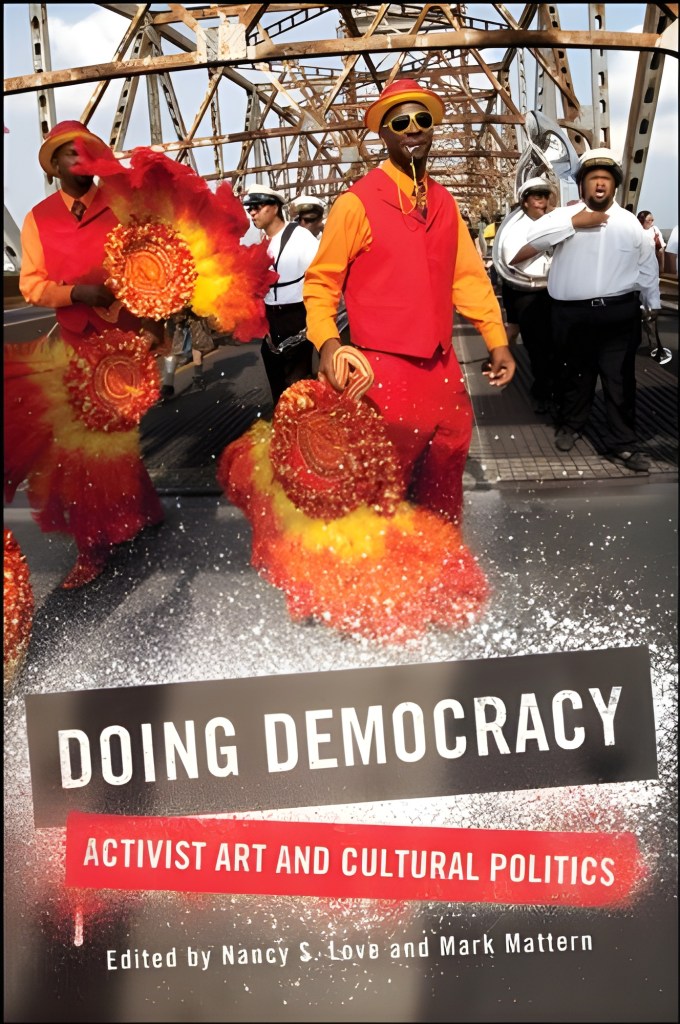

Doing Democracy: Activist Art and Cultural Politics, Edited by Nancy Sue Love and Mark Mattern, Albany, State University of New York Press, 2013, 386 Pages, ISBN: 9781438449111, ₹2423

The established frameworks of studying social movements tend to focus on rational and empirical and objective indices such as class structure, protest strategies and leadership. Nancy S. Love and Mark Mattern’s edited volume, Doing Democracy: Activist Art and Cultural Politics marks a critical intervention in the dominant methodology of understanding social movements and political activism. Moving away from a rational-legal materialist assumption of politics espoused by liberal democratic scholars, the contributors in this volume focus on the affective corporeal experience of politics most acutely perceived through artistic expression. John Locke and subsequent liberal theoreticians such as Mill, privatised the aesthetic realm of the liberal subject as a matter of individual taste (p.7). Consigning the aesthetic to the ‘private’ was an intentional cultural-political project with significant implications on how citizens understand and practice democracy. The assumption that art is apolitical has been challenged by scholars as early as Antonio Gramsci (1971)1. Thus, the liberal depoliticisation of the cultural realm- a possible arena of political struggle – potentially decreases the democratic capacity of citizens to critically evaluate the structures of domination prevailing in society.

Love and Mattern, in this volume, seek to re-politicise art through methodological and conceptual intervention. In reference to the rise of alternative aesthetic modes of public discourse, they ask whether pluralizing the forms of political communication prefigures a more democratic future by enabling citizens to exercise their share of popular sovereignty. The book has been organised into eight sections and fourteen chapters. These chapters apply theories of political science to artistic experiences and analytically link affective experiences to political realities. Artistic experiences serve as critical vantage points. They act as primary source material, autobiographical accounts, reflective secondary analyses or empirical phenomena used to understand the politics of the masses, particularly the marginalised, who have historically been excluded from formal political institutions. Each section engages with a particular mode of aesthetic public discourse – such as visual media (photography, cartoons), poetry and literature, music, theatre, parades – and how they amplify or condense democratic capabilities of citizens. The articles in this volume pursue four broad vectors of analysis.

First, art is seen as a method of making oneself visible, particularly in the context of social marginalisation. Hannah Arendt (1959) argued that in the public realm, where nothing counts that cannot make itself seen and heard, visibility and audibility are of prime importance. Situating himself in the favelas of Brazil, Frank Möller’s chapter on photo-activism connects visibility and political agency to argue that visual representation of the self via citizen-photography, transforms former subjects of the oppressor’s gaze into agents capable of democratic participation. Wairimu Njoya, in his essay, reveals how the ‘blues tradition’ in America allowed black people to communicate their suffering while keeping alive a ‘tragicomic’ hope for a better future. Songs as a form of artistic expression enabled individuals to ‘imagine’ an alternate political utopia in the most bleak of circumstances. Njoya compares this to the Kantian ‘human sublime’ where the physically unfree can ‘pretend to be free’ by exercising their moral agency.

The ‘slave sublime’, in the works of Toni Morrison, finds black people asserting their moral agency (such as Seethe in the novel Beloved) by envisioning alternate self-understanding which subvert racist stereotypes. Notably, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. both called for the exercise of internal or moral agency/freedom (swaraj) to combat external constraints. Thus, the contributions in this volume highlight the pre-figurative quality of art and popular culture to imagine democratic possibilities which remain elusive in academic literature if social movements are studied within the narrow constraints of rational ‘real’ politics. Drawing on Iris Marion Young (2000), Mattern and Love argue recognising artistic media as ‘doing democracy’ broadens the base of political participants and envisions a more deliberative and agonistic vision of democracy.

Second, aesthetic modes of discourse have made politics more accessible to the people, and thus strengthened democratic citizenship. Parades in New Orleans are analysed by Peter G. Stillman and Adelaide H. Villmoare as a locus of civic engagement and sites of articulating dissent. Popular culture augments citizenship by fostering a sense of the common good while recognising ‘difference’ with generosity and empathy- not domination and exclusion, as espoused by western rationality. Sanna Inthorn and John Street in their article on first-time voters in the United Kingdom, argue that popular culture aids political engagement by creating collective identities that provide young voters a sense of community in the midst of political alienation and apathy. They draw on and reinforce Nussbaum’s (2010) theoretical corpus by demonstrating how aesthetics amplifies the democratic capacity of citizens by counteracting insecurity over ‘difference’ through the development of empathy needed to practice democracy in culturally diverse societies.

Third, the chapters in this volume explore how aesthetic modes of discourse are democratic, not only in content but also in form. The form of slam poetry2 and verbatim theatre3 blurs the lines between creators and consumers of art. Audience interaction and authentic portrayal of complex issues on stage, enable critical deliberation on socially relevant political realities. They reclaim popular power as ‘agenda setting’ (Bachrach and Baratz, 1962) and prefigure a more participatory and democratic vision of politics. Emily Beausoleil in her article on theatre in apartheid South Africa, argues that the ‘unruliness’ of theatre defined in terms of polyphony and transience protected plays against state censorship and supported mass mobilisation through the coded language of art.

Fourth, the contributors acknowledge the internal power dynamics of artistic forms and warn that aesthetic modes of public discourse may promote reactionary politics and elitism. Love highlights the use of ‘white power music’ to augment the reach and legitimacy of white nationalism. Art has historically been an elite preserve. Despite changing currents, the high art- low art dichotomy continues to burden aesthetic discourse and threatens to sideline marginalised voices. In the context of racist cartoons about Obama, Sushmita Chatterjee in her article on political cartoons, notes that there exists different frames of perceiving visual media. Critical race theorists like Matsuda and Crenshaw argue that the use of racist language in popular media tends to dehumanise vulnerable and marginalised identities. Visceral language serves as a powerful conduit of reinforcing prevailing identity-based stereotypes that can adversely impact the exercise of constitutionally guaranteed rights by individuals belonging to historically oppressed communities. Butler (1997, 163) on the other hand argues violent or prejudiced language reveals existing social chasms and acts as a ‘trigger’ which can outrage, agitate and mobilise citizens to enact change. Thus depending on which frame is dominant, visceral visuals can either contract democracy by causing ‘injury’ or spur ‘insurrection’ through democratic change .

This volume, written in 2013, was a timely intervention in the domain of understanding performative politics. In fact it seems to have foretold the wide body of literature that has emerged in the past decade linking performance and politics.4 Today, analysing the performance of participants at protest sites and the gestures of charismatic political leaders play a crucial role in understanding the politics of resistance and populism. This volume can also be situated in the academic field of studying agonistic ‘radical democracy’, first conceptualised by Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. Laclau and Mouffe (1985) view confrontations in democracies favourably as they indicate civic vitality and pluralism. Thus, conflict in the cultural domain can also be interpreted as a sign of democratic vibrancy. It was disappointing however, to observe that while the artistic phenomena analysed in this volume extends to peripheral political events like memorials, it failed to engage with core political aesthetics like protest posters and radical cinema.

Doing Democracy has a powerful scholastic agenda- putting art on the academic map of political science. The volume’s intellectually nuanced engagement with traditionally ‘political’ concepts like E.P Thompson’s ‘moral economy of protest’ or Benedict Anderson’s ‘imagined communities’ is of crucial significance as correlating art with core political theories, establishes aesthetics as a central concern of political science and not an axiomatic preoccupation. The volume presents a convincing argument about why the study of politics and particularly social movements will benefit from the inclusion of aesthetics as a method and category of analysis. Not only does art provide exclusive intellectual insight, but its unique creative ability to envision seemingly impossible democratic utopias, sustains social movements in the realm of political action and enriches political analysis in the realm of academics. By intertwining rational and affective faculties, Doing Democracy tries to erase the false dichotomy between art and realpolitik. Afterall, as noted by Rabindranath Tagore (1931, 139), what is art, but the response of man’s creative soul to the call of ‘the real’.

Endnotes

- Writing between 1926 and 1935, Gramsci argued that the ruling class established political control by shaping dominant cultural institutions of civil society.

- A form of performance poetry that combines performance, writing and audience participation.

- A form of documentary theatre which is based strictly on testimony and interviews of real people.

- See The Oxford Handbook of Politics and Performance Edited by Shirin M. Rai, Milija Gluhovic et al. (OUP: 2021) and The Aesthetics of Global Protest Visual Culture and Communication Edited by Aidan McGarry, Itir Erhart et al. (Amsterdam University Press, 2019).

References

- Arendt, Hannah. 1959, Winter. “Reflections on Little Rock” in Dissent Magazine. www.dissentmagazine.org/article/reflections-on-little-rock.

- Bachrach, Peter, and Morton S. Baratz. 1962. “Two Faces of Power.” The American Political Science Review. 56, no. 4 : 947–52.

- Butler, Judith. 1997. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. New York: Routledge.

- Gramsci, Antonio. (1971) Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Translated and edited by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. New York: International.

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 1985. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2010. Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Tagore, Rabindranath. 1931. “The Artist”, The Religion of Man. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd: 129-142.

- Young, Iris. 2000. Inclusion and Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Suhasini Das Gooptu has recently completed her Masters from the Centre for Political Studies, JNU, New Delhi.

Leave a comment