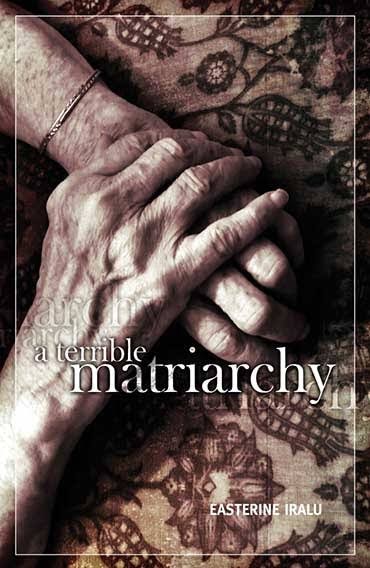

A Terrible Matriarchy by Easterine Kire, New Delhi, Zubaan, 2013, 204 pages, 20x14x4 cm, ISBN: 9788189884079, Rs 495.00 (paperback)

By Nanuma Subba

It is an unfortunate reality that stories from Northeast India are a rare find, rarer still is the subtle art of creativity that portrays complexities in simple ways. From the outset and as the title expressly suggests, A Terrible Matriarchy by Easterine Kire reflects on the subjects of patriarchy, women’s share in society and the socio-cultural context surrounding women in every wake of life, which makes for a compelling read. Through the protagonist Dielieno (Lieno), the author narrates the everyday life of women in a village in Nagaland. Set in Northeast India, the novel starts with a grandmother serving meat to grandchildren. The grandmother ladles the most desired piece of meat to Lieno’s brother and instructs that there are different portions for boys and girls. The book dwells on themes that focus on women’s share in a family—be it a share of food, division of property, or the disparate amount of housework women constantly engage in, which is right where the novel takes off.

One of the first things noticeable in Kire’s work is how it extricates the dynamics of a family inside the house. Kire, in this book, extracts intricate details at a micro-level that exposes the politics of the household. More often than not, discussions on the workings of the household are reflected in a limited manner in non-fiction, which is where works of fiction like Kire’s find its brilliance. While it is apparent in the book that the eldest woman in the house upholds the power dynamics in a household, it is also clear how the grandmother exercises internalised patriarchy and actively passes it on to her future generations too, all within the household.

The central theme of the book rests on women’s household labour. Women’s labour and leisure have been manufactured and differentiated since the formative years of early childhood. It then becomes common knowledge which dictates that women are better at performing household labour. But again, with a lifetime of training inside the house, women are bound to be skilled workers. The binary revolves around men doing the ‘heavy’ and ‘technical’ work, not necessarily out of compulsion, but as a measure of displaying their ‘strength’ and ‘masculinity’, where they can choose to be good at it or not. However, in the case of women, they are trained to be good at household labour with quality control, which is made effective by their mothers, grandmothers, or any other female figure in charge of the household. A chain of ‘duties’ in a hierarchical order of command is built in the household via the institution of family. This book reiterates these uncomfortable realities that may not find much expression elsewhere.

Therefore, as a grandmother dictates that girl-children should ‘marry and have children and be able to cook and weave cloths and look after the household’, the protagonist/narrator Lieno, a girl struggling between her current life and her little dreams, says, ‘I could not fall asleep for a long time. I thought about school and how nice it would be to learn to write and sing and draw as my brothers did’ (p. 22). This juxtaposition of two women in two different generations wanting very different things in life is portrayed in a very lucid manner. It propels to where Kire wants the reader to see how often women negotiate between these two worlds, put to test every time, in the middle of a patriarchal world where women are always taught ‘how to behave’.

As the story progresses, it resonates with women’s experiences in general, coming face-to-face with their self-sacrificing tendencies for the men in their family, and realising this fact very early on in life whilst preparing oneself for an impending one. While Lieno is fond of studying, her grandmother quickly makes her realise that the struggles of being a woman are literally between sustenance and non-sustenance — between reading or eating, when the grandmother says, ‘people can’t eat books’ (p. 28). These are not things unheard of. Many generations of women have heard such things, not only from their grandmothers but also from their mothers, who sometimes, unfortunately, propagate inherent patriarchies around the world.

Even as the book tends to relate to women’s experiences, it transports the reader to Nagaland. Kire offers a prismatic view of the geography, culture and society in Kohima. She describes how harvest depends on rain, the cruel winters in the hills with flimsy housing arrangements in the village, and the warmth of sunny days. She weaves into the story some specific cultural markers of the region for the reader to imagine the novel’s backdrop. She writes about spirits, dreams, Christianity, marriage, food, drinks, and the Battle of Kohima. Her lens traverses from inside the home to the outside, where the story travels around the village, drawing in many characters in and around the protagonist—making the story not of one woman, but of many persons. Given this vast arena of storytelling, the book occasionally risks juggling between too many stories. However, it quickly picks up and ties loose ends as it draws closer to the end.

Kire undertakes each theme in the story with careful description while orchestrating their deep metaphorical meaning. For example, when she describes beliefs like dreams as signs, she explains their prophetic character in the story, where Lieno says, ‘Isn’t it strange that dreams always come true especially if they are dreams of death in the family?’ (p. 98) Similarly, when Kire engages with the topic of food, it is descriptive of the culture in Nagaland, and the mention of meat is found quite frequently. At the same time, Kire offers a clear picture of hunger, gendered division/distribution of food, its significance and the patriarchal structure embedded in the everyday.

She unearths village life, where there are specific social interaction spots, like the village’s water spot in the book. The gossiping women at the water spot is also something that makes the story familiar. It reminded me of the water spot we had seen growing up in our neighbourhood and how we, as children, feared spirits near the water because we also knew that ‘spirits liked water’ (p. 54). When Kire ventures into death, loss and grieving, there too it is accompanied by strength, calm and forgiveness. While doing so, she also discerns that patriarchy not only affects the living but unfortunately engulfs women even after death, when she writes, ‘… and the most feared of spirits were those of old women’ (p. 180). The book ends at a sombre pace and leaves the reader with a lot to reflect on.

It is a simple story of the everyday packed with unanticipated but very intriguing twists and deep metaphors. This gripping tale of the life story of a woman is a much-awaited prose that rips open the societal mesh, and presents a picture so effortless yet daring in such profound ways. A Terrible Matriarchy is a moving story of intergenerational patriarchy. As a tribal woman from India’s Northeast, Kire’s writing gave me much solace. Representation matters, and so do stories of the everyday. Often overlooked and unvoiced, some forms of storytelling engage with the person of a reader. It alters a small part of one’s existence and contends another simultaneously. This is one such story.

Nanuma Subba is a Doctoral Candidate at the Centre for the Study of Law and Governance, JNU. She is researching ‘development’ and its effect on the environment and life of tribes in her native place, Sikkim. She aspires to be an enchanting storyteller someday.

Leave a comment