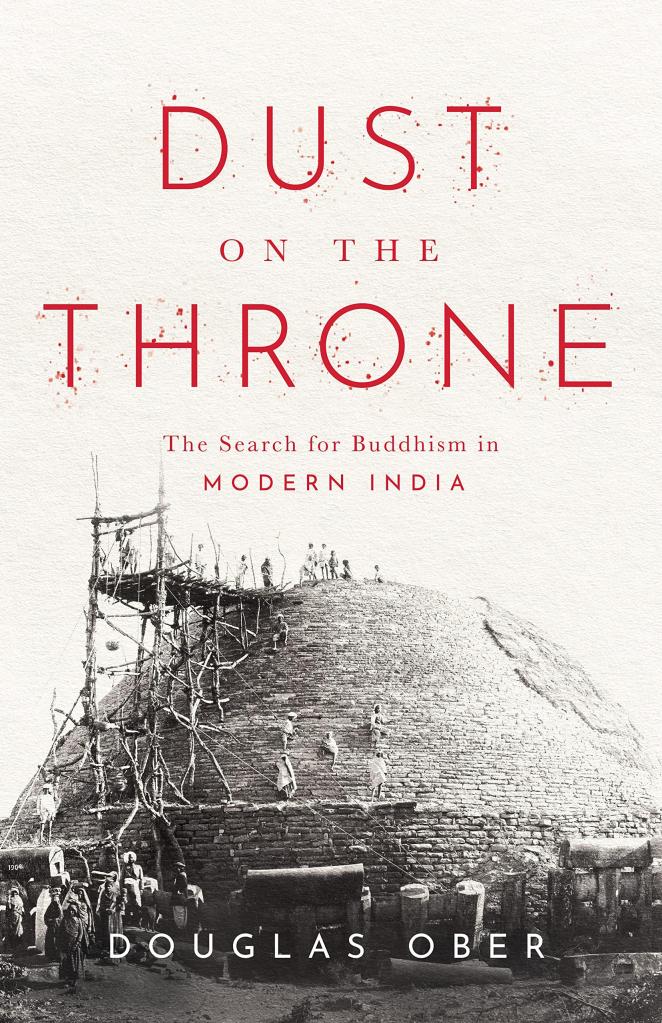

Dust on the Throne: The Search for Buddhism in Modern India, Douglas Ober, Stanford University Press, 2023, 391 pages, ISBN 9781503635036, US$ 32, Paperback.

by Pranoy Saha

Dust on the Throne is a path-breaking book in the field of history of Indian Buddhism. Scholars across disciplines dealing with modern Indian history have often been either influenced by or pushed the understanding of the marginal relevance of Buddhism outside of Ambedkar’s followers or among Himalayan Buddhists and exiled Tibetans. The 19th century marked a renewed interest in Buddhism internationally, and those who spoke of this Buddhist resurgence called it a ‘revival’. This idea of revival was based on the assumptions concerning the decline of Buddhism. While the reasons for the decline remained contested, scholars purported the view that by the 13th-14th century, Buddhism had completely disappeared from India, the place of its birth. Author Douglas Ober suggests a threefold consensus among the scholarly community regarding modern Buddhist history. Firstly, the majority of Buddhists in India are Dalits, who have continued to convert since the historic conversion of 1956 led by Dr Ambedkar. Secondly, in the 19th century, most of India’s ancient Buddhist sites were only visited by colonial archaeologists, not Buddhist monks. Thirdly, the network of Buddhist pilgrimage in India was only actively traversed by Buddhists around the world after Anagarika Dharmapala founded the Maha Bodhi Society in Calcutta in 1891.

The book challenges these assumptions, illuminating narratives, anecdotes and sources that complicate these assumptions as misconceptions. It complicates the interpretation of ‘revival’. The widely popular discourse of the absolute disappearance of Buddhism from India is critically scrutinised, and a complex history of destruction, decimation, suppression and periodic resurgence is presented. In building upon an alternative discourse on Buddhist history, the book makes four specific interventions. First, it elaborates upon the complicated history of ‘periodic Buddhist resurgences and trans-regional pilgrimage networks’ during Buddhism’s proclaimed ‘disappearance’. Second, while there was a certain decimation and decline of Buddhist institutions, it argues that their ‘colonial revival was led as much by Indians and other Asians as it was by Europeans’. Third, it evidently situated the modern Indian Buddhist revival to nearly a century before 1956. Fourth, it argues that the 19th-century revival of Buddhism ‘gave significant shape to modern Indian history, from the making of Hindu nationalism and Hindu reform movements to Dalit and anti-caste activism, Indian leftism, and Nehruvian secular democracy’ (p. 22).

The first chapter extensively deals with Buddhism during the medieval and modern times. It provides abundant details about the colonial enterprise involved in archiving, documenting, and publicising the history of Buddhism. This chapter’s major argument is related to the epistemology of this history. It argues against the popular misconception of attributing the knowledge produced on Buddhism solely to colonial figures and considering Indians to be ’empty vessels’ who had lost all memory of Buddha and his religion. This chapter highlights the complex antagonistic relationship between Buddhism and Brahmanism by closely reading medieval Brahmanical religious texts, temple chronicles, devotional poetry, songs, art, and iconography. In many instances, the native Brahmin intellectuals exhibited disdain against Buddhism and considered it an upadharma or a lesser teaching, which was rightfully defeated. These instances and their descriptions argue against the notion that Buddhism was completely forgotten but rather mark the ‘memory of struggle and conquest’ (p.61).

This form of antagonism displayed was not uniform, and many native-scholars played an instrumental role in shaping Buddhism. The second chapter explores the contributions of some of these figures, like Haraprasad Shastri, who used his B.A. (1876) and M.A. (1877) in Sanskrit from Calcutta University to traverse the journey from a ‘native Pandit’ to become one of the most influential scholars of Sanskrit Buddhist texts (p. 75). Manuscript collector and intellectual Sarat Chandra Das and Ranjendralal Mitra played a key role in establishing the Buddhist Text Society in 1892 in Calcutta. By 1915, Calcutta University offered a curriculum in Pali, Tibetan and Sanskrit, and Bombay University also had a Pali curriculum in place (pp. 110-111). The third chapter further elaborates upon the dense network of Indians and Asians who were engaged in the revitalisation of Buddhism in India. However, these local associations were anything but uniform in their approach to Buddhism. The author devises an apt allegory of a Banyan tree to depict the various branches of Buddhism in India and how they are interconnected yet distinct. For Indian elites, association with the Theosophical Society (TS) (1882) and Maha Bodhi Society (MBS) (1891) secured a particular social capital as there was a ‘growing civilisational and national pride in Buddha’s Indianness’ (p. 127). Both TS and MBS found financial and organisational support from the caste Hindu networks.

Venerable Kripasaran from Chittagong established the Bengal Buddhist Association (BBA) in Calcutta in 1882. In South India, Pandit Iyothee Thasa established the Shakhya Buddhist Society (SBS) in 1898. Both BBA and SBS worked extensively on vernacularising Buddhism, but SBS was more inclined towards enabling conversions, and BBA was primarily targeted towards Bengali-speaking Buddhist migrants from Arkan, Burma. The book delves closer into the activities of these associations to delineate the local and transnational networks they tapped into. For instance, under the aegis of SBS, the Irish Bhikkhu U. Visuddha held the conversion of 1000 workers and their families in 1908 (p. 137). Apart from these Buddhist organisations, the Hindu reform and orthodox organisations and networks also took a keen interest in Buddhism. Chapter 4 elaborates upon this history and provides evidence of popular national figures like Gandhi, Vivekananda and Tagore engaging with Buddhism. The framework under which the Hindu appreciation of Buddhism took place was a ‘double-edged sword’. On the one hand, the support of Hindu organisations and figures for Buddhism enabled an economic and socio-political affirmation of Hindu elites to the Buddhist mission. On the other hand, ‘by calling Buddhism as Hinduism and Buddhists as Hindus, Buddhist traditions were denied their intrinsic identity and autonomy, and, in effect, falsified’ (p. 182).

The title of Chapter 5, ‘The Snake and the Mongoose’, is an allegory taken from the works of medieval Sanskrit grammarians and philosophers, which refers to the antagonism between Buddhism and Brahmanism. This chapter focuses on the modern history of ‘Bahujan Buddhism’, or Buddhism of the masses in India. It provides extensive evidence to argue against the popularly held notion that Buddhism became relevant to the anti-caste movement only after Ambedkar’s mass conversion in 1956. In doing so, it explores the interactions and exchanges of Dr. Ambedkar with other Buddhist organisations and figures. It highlights the broad network of Bahujan Buddhism steered towards anti-caste agendas and their complicated relationship with Hindu organisations, donors and Buddhist advocates who towed the line of sameness between Hinduism and Buddhism. Chapter 6 focuses on the interaction between Buddhism and Communism during that period in history. Among other figures who spearheaded this dialogue between Buddhism and Communism, this chapter elaborates upon two of the most prominent ones, Dharmanand Kosambi and Rahul Sankrityayan. While the former was more inclined towards presenting the socialist essence of Buddhism, the latter adopted a more radical stance of arguing upon the limits of traditional Buddhism, which could be overcome through Marxist approaches.

Nevertheless, their intellectual and religious trajectories portray a dynamic exchange between the two ‘isms’ in India and abroad. Moreover, both of them were extensively involved with international and communist networks, were initiated into Buddhism in Ceylon, and travelled to Russia to study Buddhism. In marking the experience and life works of these figures, Ober consolidates his central argument further by saying that Buddhism’s growth in India cannot be attributed solely to Western or colonial forces, rather, it was a dialogue with the local Buddhist scholars, intellectuals and activists. Chapter 7 elaborates on the influence that Buddhism had upon the theatrics and policies of the newly formed Indian nation-state. Be it the Buddhist symbols incorporated as national symbols, the international recognition of India as the birthplace of Buddhism, the approach of relic transfers for consolidating ties with other Asian Buddhist countries, or the principles of Buddhism that guided the foreign and national policies, Buddhism certainly held much influence in shaping the Indian nation-state than has been conceded to it by political historians.

The book provides an overarching frame to make sense of the various strands of Buddhism that populate the present and traces the history of their engagements, interactions and negotiations. Even though the book does not engage directly with Buddhist practices, rituals and their symbolic meanings, it elaborates upon the various disciplines, institutions and forces that gave them life and meaning in modern India. In doing so, it mirrors the approach laid out by Talal Asad in his seminal work, ‘Genealogies of Religion’. Asad argues against the overemphasis of phenomenology in anthropology’s treatment of religion. Apart from studying the experience of religious practices and rituals, Asad asserts that ‘the possibility of religious practices and their authoritative status are to be explained as products of historically distinct disciplines (institutions) and forces’ (Asad 1993, p. 54). Ober adopts a multi-modal and multi-lingual model of research that enables him to cover the breadth of resources. As the book moves to so many figures and organisations, it makes certain compromises with depth, but that is a strategic compromise in favour of developing a ‘grand narrative’, without which ‘examples of Indian Buddhism would continue to be seen as one-off, localised instances, rarities that do not merit inclusion in wider historiography’ (p. 287). Due to obvious constraints of the project, the book does not indulge in detail with the relationship between these different spheres and organisations of Buddhism in more recent times. Nevertheless, the book provides a solid basis for future work in this direction.

References:

Asad, T. (1993). Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam. The John Hopkins University Press.

_____________________

Pranoy Saha is pursuing a PhD in Performance Studies, focusing on the intersection of

culture, religion, and politics in everyday life. His research explores the Ambedkarite and

anti-caste movements, particularly examining the role of religious conversions in shaping

these movements.

Leave a comment