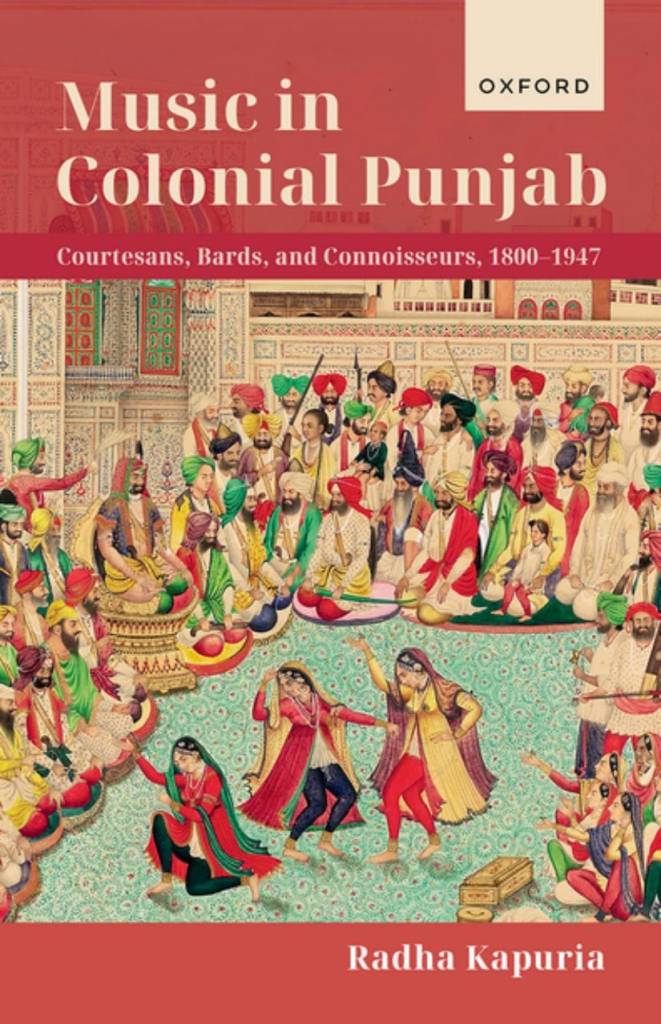

Music in Colonial Punjab: Courtesans, Bards, and Connoisseurs, 1800–1947 by Radha Kapuria, Oxford University Press, 2023, 348 pages, Online ISBN: 9780191959394, £83.33

The importance of literature, art, and culture in everyday life, offering people a sense of identity and belongingness, has captured the attention of scholars who are now unearthing the deeper meanings of people’s engagement with culture. While anthropological and cultural studies centring on ‘civilisation’ are not new and can be traced to colonial times, the intent and methodology for undertaking such studies have changed. Instead of the colonial impulse to control and dominate, basically, to master in a mechanical, bureaucratic form, as Tagore points out in his lectures on nationalism or the native elites’ response in defence through the same trope, the studies undertaken presently aim at understanding the shifts in cultural practices, exploring their dynamics and causes (Tagore, 2017, p. 55). The ethnographic methodology is used by scholars who are encumbered by the disciplinary boundary. However, Radha Kapuria’s book Music in Colonial Punjab: Courtesans, Bards, and Connoisseurs, 1800-1947 is a distinctive study of understanding musical culture in colonial Punjab, emphasizing on archival research and an analysis of paintings. The timeline of Kapuria’s work- from the nineteenth century to the year of independence is crucial due to the relevance of the nineteenth century as a marker of change when the modernist ideals made their prominent appearance in colonial India, evoking responses from the native elites.

The focus of this study is on archival methods and social and gender dynamics as opposed to an ethnomusicology and oral traditions within the disciplinary silo, which forms the conventional methodology for such a study on music culture. This has contributed to the richness and interdisciplinarity of the study, making it carve out its own space, opening the way for other such studies. The book can be viewed from the perspective of the inner/outer dichotomy and the rough periodisation of colonial India provided by Partha Chatterjee. For Chatterjee, while the outer realm of statecraft was seen as British supremacy, the inner realm of spirituality and culture was viewed as the stronghold of native Indians, where they exercised autonomy and sovereignty. However, it is the changes that took place in the inner realm in response to its contact with colonial modernity that greater transformations begin to take place (Chatterjee, 1993, p. 6). Chatterjee also points to the shift in focus of the Indian reformers, who initially sought support from the colonial government in bringing reforms related to traditional practices and institutions but later on resisted colonial intervention in matters pertaining to ‘national culture’ (Chatterjee, 1993, p. 6). The book adds to this scholarship by showing the reception of the Punjabi musical sphere to the colonial modernity and complexities therein.

Four detailed chapters in the book, with the introduction that clearly and broadly lays out the aims and hypothesis of the research and the conclusion summing up the research, offer a broad range of the stature of music, musicians, and dancers in colonial Punjab before and after the exposure to colonial modernity, highlighting the aspects of gender, class and connoisseurship of the native rulers.

Kapuria argues against the labelling of Punjab as a bearer of rustic culture and attempts to dismantle the conventional distinctions between folk and rural versus classical and urban. As this objective runs across the text, each chapter takes up two major themes and shows the fluidity of culture in Punjab that defies classical versus rustic dichotomy, which undergoes transformation with the exposure to colonial modernity, whereby the fluidity is replaced with desperation for categorisation and bureaucratisation. The book expands on the complex trajectory of musical history in Punjab with an intermeshing of British and native perceptions, leading to shifts in not only natives’ ideas related to music and who should be allowed in the musical public sphere (Muhammuddin’s Mirasinama) but also how some British missionaries (like Anne Wilson and Miriam Young) found value in and used natives’ musical culture for propagation activities. Anne Wilson, in particular, had a change of heart after she saw a young, rural boy singing and simultaneously performing acrobatics. The performance moved her, making her ‘a lifelong student of Indian music’ (Kapuria, 2023, p. 139), who wished the British government to understand the cultural ways of the natives.

As Kapuria mentions,

“the experience of listening to a ‘haunting song’ awakened in Wilson a desire to more completely understand the ‘natives’. She was seemingly pushed to a re-evaluation of the imperial encounter, recognizing the common humanity of both colonizer and colonized” (Kapuria, 2023, p. 139).

Bringing Chatterjee’s distinction of the inner and outer domain, one can view Wilson’s argument as a suggestion for the British government to make excursions into the inner domain of the natives but (very importantly) with the intent of understanding them.

The book begins with the aspect of gender, the power and status upheld by courtesans who are in the art of music and dancing in Ranjit Singh’s court, with recurring mentions of his Lahore and, occasionally, Rapur Darbar (court). The spotlight on women is evident in Ranjit Singh’s actions, such as his marriage with the two renowned courtesans, Bibi Moran1 and Gul Begum, he married out of love instead of a strategic alliance. Adding to such decisions is his deployment of ‘Amazonian’ dancers (mostly Kashmiri), dressed in military attire and performing with swords, as a way to show the Court. Kapuria’s extensive description of Ranjit Singh’s courts and the stature of female performers appears eloquent. Instead of simply glorifying the high status of courtesans, she showed Ranjit Singh’s continued exercise of control over courtesans. Kapuria points out that ‘they played an essential part in Ranjit Singh’s crafting of unique state rituals symbolising his power to outsiders’ (Kapuria, 2023, p. 62). Although he defied Sikh orthodoxy and continued to favour courtesans, his strategic use of Amazon women, a tactical approach symbolising his power over conquered territories and rivals, shows the instrumentalisation of courtesans.

Following the approach of tackling two themes in one chapter, the second chapter moved on from Courtesans to Mirasis on the one hand and the advent of missionaries on the other. Mirasis, a marginalised, hereditary, nomadic group of bards who performed in classical and folk music culture along with Kanjirs, another lower caste group of performers, some of whom became elite tawaifs.

Kapuria significantly focused on Muhammaduddin’s text, ‘Mirasinama’ and underlined how reform of the contempt along with the proposal for reform of the community was presented by him, which raises apprehensions about his positionality with respect to the Mirasis community.

From Mirasis and missionaries, the text moves on to musical Publics in Lahore, Amritsar and Jalandhar2. It is in this chapter that Kapuria directly and extensively tackles what can be called the ‘renaissance of music’ in Punjab, whereby the native elites took up the project of modernising music by ‘cleansing’ the musical space from female performers and ‘reforming’ it by shredding all hints of eroticism while imposing the devotional aspects to it. The rationale offered for selecting Lahore, Amritsar, and Jalandhar is the existence of ‘a Lahore-Amritsar-Jalandhar musical network’, which linked the distinct histories and demographics of these areas. Further, cities gave more autonomous spaces to women performers, thereby making them important to study. The ease of access to enormous written materials, either historically present or sourced from cities, also added to the convenience of selecting cities for the chapter. The author has also accepted that even though her focus remained on these cities selected by her, the significance of the village and the folk culture cannot be downplayed. However, it appears that the chapter does not sufficiently deal with all three areas, and the customary two aims involving a focus on cities and the Renaissance seem to be a little too broad, thereby lacking in greater depth. In an attempt to explain everything, the chapter appears a little haywire and disconnected in some places. For instance, while modernity, cities and anti-nautch campaigns are interrelated themes, the seamless flow of one theme is interrupted by the other instead of flowing from the prior one. For instance, while the section on Purity Soldiers and anti-nautch activism ended with musical gatherings for reform organisations, like Arya Samaj, Brahmo Samaj, and the Deva Samaj, the next section moved on to piety in music from invoking Bulleh Shah to Islamic, Sikh and then Hindu reforms in the next sections, thereby going broader by taking in varied religious reforms instead of going deeper into each one of them. Further, the section on Punjab’s women entering the Hindu musical reform sphere is interrupted instead of complemented by an explication of the role of Pt. Vishnu Paluskar in the Hindu reform movement and the discussion on nationalism, post which the discussion again brings in the women’s role in the section ‘Punjab’s First Woman Writing on Music’, thereby indicating disjunctures and a need for a smoother flow. The chapter, however, shows the stark contrast from the times of Ranjit Singh when courtesans wielded considerable power and status despite British rulers’ disapproval of them and perceiving them as promiscuous to the times when the natives accepted British notions of modernity and relegated courtesans to the margins, filling the musical public space with ‘chaste middle-class women’ (Kapuria, 2023, p. 19). This reformist period marked by the adoption of British modernist norms in Punjab’s musical sphere is reflective of the large-scale trend since a similar perception of doing away with erotic writings can be identified in the Hindi public sphere where magazines like ‘Balabodhini’ edited by Bharatendu Harischandra had writings referred to as Stri Upayogi, useful for women in terms of domestic chores and becoming ‘ideal women.’

The ‘cleansing’ modernist shift in the musical sphere is also similar to the shift in the relegation of Braj Bhasha, shringar rasa for the Sanskritised Hindi, and veer rasa echoing nationalist undertones (Gupta, 2000). Therefore, the chapter indicates the shift in the Punjabi music sphere whereby the significant change in the form of the replacement of actors and the content of music transformed the sphere altogether. Further, this change was led not by the British rulers but by the natives who accepted the modernist norms.

The last chapter focuses on the Patiala and Kapurthala Gharana, in contrast to the popular cities of Lahore, Amritsar and Jalandhar. In tandem with the larger objective of the book, the chapter traces the dynamics between elites and subalterns (Rababis, Dhandhis, Mirasis) in the musical sphere, whereby attempts were made to sideline the latter who resisted such treatment, particularly in the form of letters. While Patiala embodies an amalgamation of religious, devotional gurbani music, a more secular Hindustani music by kalawants, Kapurthala embraced Westernisation in a greater capacity, in the form of interactions with Western musicians, sponsoring the interested Westerners to learn native music. Patiala’s robust and vibrant culture was not limited to music and percolated into art, architecture and literature as well.

Three interesting points that stand out in the chapter include, first, the increasingly rational and bureaucratic appointment and remuneration process of musicians in Patiala and Kapurthala, which was marked by a financial crunch. Second, the archival records in Patiala indicate the dominance of male musicians (involved in devout Sikh songs), thereby hinting at the push away of the earlier women performers from the musical space. Third, the formation of Sangit Sabha, as a middle-class association fashioning itself as a modernist, indulged in devotional songs, marginalising the hereditary lower caste groups like Rababis, Dhandhis and exhibiting elite norms, supported by the royal court, leading to the high membership fee and tickets for concerts. The ‘cleansing’ (of lower caste -traditional musicians) and ‘reforming’ (from sensual to devotional verses) undertaken by Sangit Sabha reminds one of Hindi Sahitya Sammelan or Nagari Pracharini Sabha, which aimed at advancing the cause of Sanskritised Hindi ‘cleansing’ it of Urdu words and personalities and doing away with all forms of sensual or erotic content.

Kapuria’s research adds a layer to this expansive scholarship by showing through examples of Mai Bhagavati (female preacher of Arya Samaj) and Devki Sud (writer of Sangit Prabha, a book on music instructions published in the 1930s), of middle-class women subscribing to the gender norms of ‘ideal’ womanhood which involved marginalising the Courtesans. Bhagavati and Sud were the only women who represented themselves instead of being represented by the males; therefore, they were referred to in detail by Kapuria.

The possible reason is the probable aim of sustaining the domain controlled by males. However, further research is required to truly understand whether women have accepted the ‘modern’ gender norms or merely conformed to the dominant ideas out of the need to secure their position in the space. As the chapter also shows, the reformist organisations such as Lahore Brahmo Samaj, Arya Samaj, Sanatan Dharma Sabha and Gandharv Mahavidyala, while claiming to be modern and reformist did not offer ‘alternative modernity,’ instead followed the same recourse as that of the British rulers.

True to its title, the book recovers the history of music in colonial Punjab by debunking the label of rustic and folk music for Punjab, which runs in the background throughout the book with special focus on the aspect of fluidity from folk to classical and the expertise of musicians in Hindustani music. However, the more direct focus has been on the aspect of gender and lower caste bards. The marginalisation of the courtesans, the female performers who were once wealthy and wielded enormous power and the continued censure faced by Mirasis, the talented bards who were ridiculed by the natives on the pretext of greed or divergence from Islamic codes, appear to be forming the core of the text. The latter two chapters on renowned cities and gharanas, with a focus on patronage and bureaucratisation, are equally informative but also seek to indicate the shifts in the music sphere and their impact on the prominent actors of the music sphere. Kapuria’s attempt at ‘reading against the grain’ to bring into focus the voices of female performers, showing their literary intellect and talent as against the courtesans of Bengal, is surely praiseworthy. The use of archival methodology, along with deep analysis of paintings to draw conjectures and unearth the unpopular actors in the musical sphere, is equally noteworthy.

Although every research has a limited scope and not everything can be explained in just one book, there are certain interesting pieces of information and instances which could have been explained in greater detail. For instance, Khairan in the court standing up for her rights against violence, which was covered by the journalists and drew a large audience, could have been elaborated since the idea of courtesans using the colonial legal setup indicates their claiming of the status as ‘citizen’ instead of a non-conformist ‘outsider.’ Further, the idea of obscenity and Victorian modernist standards of an ‘ideal’ middle-class wife who is chaste and can exhibit courtesan-like features and behaviour only in front of her husband requires more elaboration. Another interesting dimension of mobility highlighted in the text Kapuria mentions is that the greater mobility of the courtesans can leave readers wanting more information on the same. Even the aspect of strategic resistance by the Mirasis from enumeration, whereby they avoided sharing details about themselves, could have been expanded in terms of other instances of defying the colonial technology of rule. Finally, the dimension of religion (for instance, the fluidity of performing for both Hindu and Muslim audiences by Mirasis) and whether it has an impact on the marginalisation of Mirasis and the courtesans, though mentioned in passing, could have been explained in greater detail.

Against the backdrop of antagonism that continued since Partition in 1945, the book hints at the hope of uniting hearts across borders through shared folk songs, similar to what shared languages do. Through intriguing details, the book skilfully argues against the labelling of Punjabi music as purely folk. It opens up discussions on the role of the rulers in advancing music in Punjab and North India. It also indicates the scope for research in exploring the resistance strategies of the marginalised groups belonging to the field of music amidst sidelining by the other sections of society, like the middle class.

Endnotes

- The personality behind the construction of the iron bridge over the Hansli canal, called Pul Kanjri or Pul Moran.

- The author also notes that these three areas, separated by international borders since 1947, were located on the Grand Trunk Road in the sixteenth century.

References:

Chatterjee, P. (1993). The nation and its fragments: Colonial and postcolonial histories. (1994). Choice Reviews Online, 31(11), 31–6175. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.31-6175

Orsini, F. (2009). The Hindi public sphere 1920–1940: Language and Literature in the Age of Nationalism. Oxford University Press.

Gupta, C. (2000). “Dirty” Hindi literature. South Asia Research, 20(2), 89–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/026272800002000202.

Kapuria, R. (2023). Music in colonial Punjab. In Oxford University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192867346.001.0001

Tagore, R. (2017). Nationalism. Penguin. India.

__________________________

Sakshi Wadhwa is a doctoral student at the Centre for the Study of Law and Governance, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India. She is working on the idea of the people and peoplehood in terms of cultural artefacts, the state, and popular mobilizations. Her research interests include the confluence of culture and politics, law and society, and social stratification in the construction of peoplehood in India.

She can be reached at: wadhwaduomo@gmail.com

Leave a comment