Ambedkar’s thoughts on Nationalism

The rich corpus of studies on Ambedkar’s invaluable contribution in striving against the injustices faced by the ‘Untouchables’ in India, and drafting the Indian Constitution which has stood the test of time, often presents his political thought as confined to his refutation of caste-based atrocities, and in juxtaposition with Gandhian thoughts on the same. Ambedkar’s ideas on nationalism are usually portrayed by the reactionary right-wing as contradictory to Gandhi or other leaders like Nehru, specifically with respect to the partition of British India. This commentary seeks to explore Ambedkar’s thoughts on nation and nationalism, particularly in the context of the creation of Pakistan, and to point out the rationale for his dissent from other leaders, along with understanding the idea of community from his political thought. Further, the commentary also deals with the intra-community dimension as viewed by Ambedkar. For Ambedkar, it is the feeling of oneness and fellowship within, and among, communities that forms the basis of a nation.

Concepts of Nation and State

For Sudipta Kaviraj, the distinction between the state and the nation lies in the fact that the former has “some elements of material, institutional fixity” while the nation “is just an idea – one of the most indefinable, intangible and yet emotionally forceful concepts affecting political action in the modern world” (Kaviraj, 2019, p.13). Further, he viewed nationalism as “an unprecedented connection of intimacy and ownership between political subjects and their state” (Kaviraj, 2019, p.14). According to Kaviraj, the simplistic story of nationalism views nationalism along with capitalist economic strength that facilitated the Western countries to establish dominance across the world. The fascination with this power derived from nationalism led other countries to adopt it. Since it was not a herculean task for Asian countries to equip themselves with the military techniques of Western countries, the reason for the latter’s dominance and emergence as colonisers lay in their power as nation-states, something which was the Western invention. The invention of the nation-state involved “a peculiar organization of emotion behind their state apparatus, and the chemistry of an affect that produced an unprecedented figuration of collective intentionality and collective action” (Kaviraj, 2019, p. 14). The strength of this force called nation-state and the Western version of nationalism appeared attractive to the elites in India, who were eager to emulate it despite the fact that neither ‘nation’ nor ‘state’ in the Western connotation of the terms, existed in India. A crucial aspect of the nation-state is the concept of sovereignty, or in simple terms, the nation is to be ruled by those belonging to the nation and not a foreign power. However, it was not sovereignty that was the root cause of worry for thinkers like Gandhi and Tagore; sovereignty was the most important component as a collective, but it was the state as a locus of all political activities and concentration that appeared problematic… The denial of sovereignty to the natives is what charged the nationalists to demand it intensively. In other words, it is state-centrism as nationalists’ aspiration that posed the major issue for Gandhi and Tagore. For Gandhi and Tagore, the nationalists’ acceptance of the all-encompassing structure of the modern state—which absorbed the freedoms once enjoyed at the societal level and erased the distinction between the political and the social—was a cause for concern. Both of them were weary of the “logic of the modern state, and techniques of modern power,” which involves a dominant political sphere with its focus on homogeneity even when it is ruled by the natives (Kaviraj, 2019, p. 20). As pointed out by Kaviraj, “Tagore argued passionately that India had never known a concept like the nation whose feeling of community was based on peoples’ common link to the political power of the modern state. And, as becomes apparent through the narrative developments of his novel, Gora, his major concern was about the homogeneity demanded and celebrated by the ideal of the European nation-state” (Kaviraj, 2019, p. 20)

Prior to colonial rule, the political and social spaces were distinct from each other, thereby ensuring that the social regulates itself and remains largely unaffected by the changes in the political one. Partha Chatterjee has also elaborated on the different socio-political set-ups in precolonial India. For Chatterjee, the political independence from British rule revealed just one aspect of anti-colonial nationalism in India; another crucial aspect that did not garner much interest was the social realm, which was fairly insulated from direct British influence. He argued that although India was a British colony politically, people experienced autonomy and independence at the societal level. In other words, British influence was limited to matters like statecraft, economy and even science and technology, categorized as “outside” domain, and people were free to follow their culture and traditions in what is categorized as the “inner” or “spiritual” domain (Chatterjee, 1993). Initially, the Indian reformers keen on reforming the traditional institutions and customs asked the colonial authority to intervene in the inner domain. In the latter phase, a reversal of this could be witnessed as although reform was still desired, there was resistance to the Western colonial intervention for the same. This latter phase that kept Western influence out of the “national culture,” for Chatterjee, is already the phase of nationalism. However, the inner domain changed where a non-Western “modern” national culture was crafted. Therefore, it was in this inner realm that the nation was imagined, already sovereign and autonomous, although politically, the colonial rule continued (Chatterjee, 1993). In short, the imagination of community in postcolonial India was dominated by the history of the postcolonial state, where the communities have a subordinated position and are overpowered by the state.

Similar to Chatterjee’s argument, Kaviraj points to the critique by Gandhi and Tagore, which is centred on the modern Western conception whereby the state takes centre stage for both political and social spaces, becoming the locus of every political and social activity. Kaviraj points out that “Tagore called this evil ‘the nation’ and an attachment to it the sentiment of nationalism” (Kaviraj, 2019, p. 27).

The resistance to supporting the idea of state centrism can rightfully lead Nandy to not view Gandhi and Tagore as nationalists; however, through this claim, Kaviraj lays out two interpretations of nationalism, which were different from the frequently cited civic and ethnic forms of nationalism. The first interpretation of nationalism deals with the anti-colonial sentiment whereby the “rule of one people by another” is considered inappropriate. It is this anti-colonial nationalism that focused on driving the British rulers out of India. The second kind of nationalism implies “a sense of cohesion among a group of members of a state that they are its ‘nation’, the people to whom the state belongs, who ‘own’ the state; which immediately produces the implication that those who cannot crowd into that definition are its internal others, marooned inside its borders but outside its collective self-definition” (Kaviraj, 2019, p. 27). While Kaviraj placed Tagore in the first category and probed into the question of whether the nation-state is the only form of political organisation for governance in the modern world, it is worthy to discuss these two forms of nationalism, which implies internal exclusion on which Ambedkar’s thoughts hold value and relevance.

Before delving into Ambedkar’s views on the two forms of nationalism, it is helpful to first note that Ambedkar faced backlash on account of his views on nation and nationalism. Most nationalists criticised Ambedkar as a ‘desh drohi’ (Guru, 2016). Ambedkar deals with the cause of anxiety of the nationalists, particularly the Hindu nationalists, to establish that India has been a ‘nation’ with Muslims as a part of it. He follows a three-step explanation to quash such claims by the Hindu nationalists, which are seen and criticised as being supportive of the creation of Pakistan.

First, he debunks the similar characteristics logic for claiming the oneness of Hindus and Muslims. For Ambedkar, while it is unrefutable that Hindus and Muslims have commonalities, such as belonging to the same race, speaking the same language, and some common traditions, believing that such commonalities indicate the same ‘nation’ was a flaw. The rationale provided by him for finding flaws in such a belief is as follows:

“But the question is : can all this support the conclusion that the Hindus and the Mahomedans on account of them constitute one nation or these things have fostered in them a feeling that they long to belong to each other. There are many flaws in the Hindu argument. In the first place, what are pointed out as common features are not the result of a conscious attempt to adopt and adapt to each other’s ways and manners to bring about social fusion. On the other hand, this uniformity is the result of certain purely mechanical causes. They are partly due to incomplete conversions…. Partly it is to be explained as the effect of common environment to which both Hindus and Muslims have been subjected for centuries….Partly are these common features to be explained as the remnants of a period of religious amalgamation between the Hindus and the Muslims inaugurated by the Emperor Akbar, the result of a dead past which has no present and no future….There is, therefore, little wonder if great sections of the Muslim community here and there reveal their Hindu origin in their religious and social life” (p. 33).

Second, he shows that the claim of being a ‘nation’ encompassing both Hindus and Muslims and, therefore, fit for self-government is faulty by putting forth the qualification of a shared, common past for being a ‘nation,’ which is inspired by Ernest Renan’s thoughts on the nation. Ambedkar points out:

“Firstly, the Hindu felt ashamed to admit that India was not a nation. In a world where nationality and nationalism were deemed to be special virtues in a people, it was quite natural for the Hindus to feel, to use the language of Mr. H.G. Wells, that it would be as improper for India to be without a nationality as it would be for a man to be without his clothes in a crowded assembly. Secondly, he had realized that nationality had a most intimate connection with the claim for self-government. He knew that by the end of the 19th century, it had become an accepted principle that the people, who constituted a nation, were entitled on that account to self government and that any patriot, who asked for self-government for his people, had to prove that they were a nation” (Ambedkar, 2014, p. 28-29).

Therefore, aligning with Tagore’s ideas, Ambedkar viewed sovereignty or self-government as a major goal for which nationalists were striving to achieve the same, and the claim of being a ‘nation’ was highlighted. Referring to Ernest Renan’s views, and agreeing with the same, Ambedkar believed in the need for common, shared glories of the past as a vital criterion to be called a ‘nation.’ Ambedkar then applies this qualification in the Muslim and Hindu communities. For Ambedkar, Hindus and Muslims have a contentious past.

“Their past is a past of mutual destruction—a past of mutual animosities, both in the political as well as in the religious fields. As Bhai Parmanand points out in his pamphlet called “the Hindu National Movement”,— “In history the Hindus revere the memory of Prithvi Raj, Partap, Shivaji and, Beragi Bir, who fought for the honour and freedom of this land (against the Muslims), while the Mahomedans look upon the invaders of India, like Muhammad Bin Qasim and rulers like Aurangzeb as their national heroes.” In the religious field, the Hindus draw their inspiration from the Ramayan, the Mahabharat and the Geeta. The Musalmans, on the other hand, derive their inspiration from the Quran and the Hadis. Thus, the things that divide are far more vital than the things which unite” (Ambedkar, 2014, p. 36)

Another recourse offered by Renan and accepted by Ambedkar is the willingness to forget the past and the emphasis on co-existing together that can still ensure the national configuration.

However, Ambedkar points out:

“The pity of it is that the two communities can never forget or obliterate their past. Their past is imbedded in their religion, and for each to give up its past is to give up its religion. To hope for this is to hope in vain” (Ambedkar, 2014, p.37).

Therefore, since the two communities uphold religions which had conflicting pasts, in order to forget the past, the element of religion needs to be forgotten, which in itself is impossible. Another aspect pertaining to the territory is mentioned later.

Third, Ambedkar distinguishes between a community and a nation, and is of the view that the demand for a separate nation by Muslims who earlier characterised themselves as a community, cannot be a sufficient reason for refusing their claim. Therefore, the will for separate existence, as pointed out by Renan, remained absent among the Muslims since they articulated their desire to break away. In his words:

“To say that because the Muslims once called themselves a community, they are, therefore, now debarred from calling themselves a nation is to misunderstand the mysterious working of the psychology of national feeling. Such an argument presupposes that wherever there exist a people, who possess the elements that go to the making up of a nation, there must be manifested that sentiment of nationality which is their natural consequence and that if they fail to manifest it for sometime, then that failure is to be used as evidence showing the unreality of the claim of being a nation, if made afterwards. There is no historical support for such a contention” (Ambedkar, 2014, p. 37-38).

He further stated:

“It is no use contending that there are cases where a sense of nationality exists but there is no desire for a separate national existence. Cases of the French in Canada and of the English in South Africa, may be cited as cases in point. It must be admitted that there do exist cases, where people are aware of their nationality, but this awareness does not produce in them that passion which is called nationalism. In other words, there may be nations conscious of themselves without being charged with nationalism. On the basis of this reasoning, it may be argued that the Musalmans may hold that they are a nation but they need not on that account demand a separate national existence; why can they not be content with the position which the French occupy in Canada and the English occupy in South Africa ? Such a position is quite a sound position. It must, however, be remembered that such a position can only be taken by way of pleading with the Muslims not to insist on partition. It is no argument against their claim for partition, if they insist upon it” (Ambedkar, 2014, p. 38).

In the aforementioned words, it is evident that Ambedkar did not discourage the attempts by Hindu nationalists to convince the Muslims to stay in unified India; however, he also highlights the validity of the wish and claim of the Muslims to break away and form a separate state.

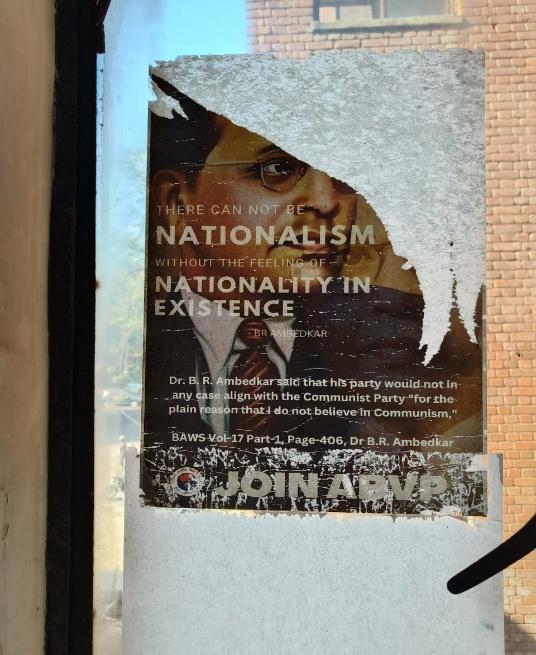

It is also worth noting that Ambedkar accepts the existence of a sense of nationality but no wish for a separate statist existence. Therefore, Ambedkar distinguishes between nationality or national feeling and nationalism. To quote him directly offers better clarity:

“First, there is a difference between nationality and nationalism. They are two different psychological states of the human mind. Nationality means “consciousness of kind, awareness of the existence of that tie of kinship.” Nationalism means “the desire for a separate national existence for those who are bound by this tie of kinship.” Secondly, it is true that there cannot be nationalism without the feeling of nationality being in existence. But, it is important to bear in mind that the converse is not always true. The feeling of nationality may be present and yet the feeling of nationalism may be quite absent. That is to say, nationality does not in all cases produce nationalism. For nationality to flame into nationalism two conditions must exist. First, there must arise the “will to live as a nation.” Nationalism is the dynamic expression of that desire. Secondly, there must be a territory which nationalism could occupy and make it a state, as well as a cultural home of the nation. Without such a territory, nationalism, to use Lord Acton’s phrase, would be a “soul as it were wandering in search of a body in which to begin life over again and dies out finding none.” The Muslims have developed a ‘will to live as a nation’. For them nature has found a territory which they can occupy and make it a state as well as a cultural home for the new-born Muslim nation” (Ambedkar, 2014, p. 38-39).

However, this does not imply that geography or territorial or administrative congruity is the only criteria for a nation. By offering the example of administrative unity between India and Burma (present-day Myanmar) till 1937, it is argued that the common sense of belonging, the feeling of nationality (kith-kin associational feeling) is what constitutes the most crucial aspect of nationalism.

According to Ambedkar, despite having the feeling of nationality, communities can co-exist within the same nation; however, the sense of nationality metamorphoses into nationalism when the desire for a separate existence of the community steps in. Nationality is, therefore, a crucial stepping stone in leading towards nationalism; however, it is not mandatory that the sense of nationality will always intensify and evolve into nationalism. In order to transform into nationalism, the desire for a separate national existence is needed, along with the existence of a specific territory which could be formed into a state for the proposed nation. Further, Ambedkar views nationality as “a social feeling” that binds individuals together with feelings of kith and kin. Calling it a “double edged sword,” Ambedkar points to the cohesion, oneness, and belonging for the community as part of the sense of nationality (irrespective of economic and social differences), as co-existing with the feeling of exclusion or “anti-fellowship” for those not considered a part of the nationality (Ambedkar, 2014, p. 31).

It can, therefore, be argued that Ambedkar tilts towards the ethnic conception of nationalism while referring to nationality, while simultaneously accommodating the civic conception by pointing to the examples of Canada (French population) or South Africa (English population), that the different nationalities subsumed under the same ‘nation’ is also possible. His emphasis on the community as legitimate decision makers in this regard points to his liberal, non-state, and non-majority centric approach whereby coercion or cajoling of the community to not break away is opposed by him; the example of Muslims’ freedom to separate acts as a prime example for this. However, a pertinent question emerging from this discussion on Ambedkar’s views on nationality and nationalism is: what should be the exact procedure, process, strategy or way of deciding whether it is the elites of the community who decide for nationalism, i.e., a separate national existence, or the community as a whole. Since Ambedkar emphasised the injustices within the Hindu community, it is reasonable to question the similar faultlines in other communities, too, thereby posing the question of ‘how’ a community decides on launching nationalism, i.e., separate existence. Further, it appears that despite attempts at avoiding it, Ambedkar falls into the Western concept of homogeneity of nations by allowing the congruity of ethnic communities with the territory while finding this geographical unity as secondary.

Navigating Emotions in the Community

Since the feature of emotions in the context of nationality is quintessential in Ambedkar’s thoughts, it is worthy of understanding to some greater length by invoking Rajeev Bhargava’s views on the same and to grasp the ways in which emotions were used by Gandhi, Nehru, and more broadly the Congress party in calling for Hindu-Muslim unity in undivided India and the response to the same by the Muslim League. For Bhargava, “a failure to achieve the objective of living within a single, unified state (it is established fact that till 1940 political separation was not on the agenda of the Muslim League) is to be explained not just by economic or religious causes but by a lack of political imagination – shaped as it was, as much by distinct conceptions of nation and community, as by differing emotions” (Bhargava, 2000, p. 194). The emotional appeals are expressed by both Gandhi and Nehru, cited by Bhargava when the former said that wished for “not a patched up thing but a union of hearts based upon a definite recognition of the indubitable proposition that swaraj for India must be an impossible dream without the indissoluble union between the Hindus and Muslims of India” (Bhargava, 2000, p. 198). The latter also made an emotional appeal for a “conscious effort on the part of all of us for the emotional integration of all our people” (Bhargava, 2000, p. 198). However, the response of the Muslim League to emotional bonding was derived, according to Bhargava, from self-interest. While he believed that Hindu-Muslim relations went through a rough patch, emotional bonds based on mutual respect might have improved them, but the emotional appeal and interest-based dynamics acted as roadblocks.

For Bhargava, a community is “a dense network of relations binding members into a thick unity of purpose. Fusion rather than the diffusion of identity is critical to this conception. Furthermore, these bonds of solidarity must be experienced emotionally, if they are to exist or else at best they exist very weakly” (Bhargava, 2000, p. 198). Therefore, the vital components of ‘community’ in general are a strong sense of purpose and emotional bonds of solidarity. It is the shift in the understanding of community whereby Hindus and Muslims were now viewed as two distinct emotionally associated communities with a common sense of purpose within themselves that the perception of each being a nation came to the fore. Therefore, what Ambedkar characterised as nationality is what Bhargava denoted as community. For Bhargava, the perception of being a distinct community with a thick sense of purpose and emotional bonding leads to a feeling of being a ‘nation’, and demand for a separate nation-state; Ambedkar placed emphasis not merely on the sense of being a distinct nationality but on the will to demand a separate nation-state that results in a separate national existence. On the one hand, owing to this rationale laid out by Bhargava, he found the terms ‘communal’ and ‘national’ becoming “antithetical to each other” during the nationalist struggle (Bhargava, 2000, p.199). On the other hand, the earlier mentioned reasons: shared past and will to live, led Ambedkar to view Hindus and Muslims as never a singular community or nationality even prior to the nationalist struggle.

A question that emerges here is whether the wish by the Congress for a unified, undivided India with both Hindus and Muslims living together is also derived from self-interest and masquerading in emotional appeals, something that, as Bhargava notes, Muslims were already suspicious of. For Bhargava, the focus on emotional appeals by the Congress leadership appeared to be based on the passion for unification without attempting to understand the reality of growing estrangement between the two communities, while Muslims, threatened by the hegemonic rule by the majority Hindus, based their demands on self-interest. Therefore, “a sentimental conception of community affected the perception and evaluation of inter-community conduct” by both communities, thereby indicating the importance of emotions in community dynamics (Bhargava, 2000, p. 199). Therefore, in line with Ambedkar, Bhargava also points to the growing emotional distance between the communities, which for Ambedkar, had always existed due to differing pasts, and any coercion in this regard should be avoided.

Intra-Community Dimension

In the context of intra-community dynamics, it is important to understand Ambedkar’s views on the Hindu community along with his staunch opposition against the caste system, which forms another important aspect of Ambedkar’s ideas on belongingness within a religious community.

As per Ambedkar, the caste system is premised on a mindset; a change in the state of mind is needed to do away with the caste system. The root cause for such a mindset is not an unfounded misconception but religious sanctions. He argued that “To ask people to give up caste is to ask them to go contrary to their fundamental religious notions” (Thorat & Kumar, 2008, p. 291). Therefore, he emphasised two kinds of religious basis, one based on rules or principles, which he found important regarding reforms. “Religion of Principles” alone can be considered “a true religion” instead of one based on ‘rules.’ Principles are different from rules because they contain the scope of judgement and reflexivity (Ambedkar, 2002). As Rinku Lamba has pointed out, the rules absolve the doers from responsibility for the actions and prescribe a format to follow in actions, while no such prescription is involved in the case of principles (Lamba, 2019).

Furthermore, since Hinduism believed in the social system to be prescribed by “Prophets or Lawgivers” and, therefore, perceived as final and unchanging, that negates the scope for reflexivity and change in accordance with the changing times and conditions (Ambedkar, 2002, p. 299). Furthermore, as eloquently pointed out by Rinku Lamba, since Ambedkar found religion in general to be not very accepting of change, and the caste system features as part of the Hindu religion, the scope for change or reform within the Hindu community appeared negligible, thereby leading Ambedkar to put in efforts to bring in the reforms, primarily to prevent caste-based atrocities, through the state apparatus (Lamba, 2013, p. 190).

The question impending for an answer here is if the state apparatus can be used for reforming the religious community, and if possible mischief can be done by using the state apparatus for quelling the demands for separation by a community through affecting changes from within their fold. For instance, the co-optation of elites by the government in the secessionist movement of Punjab or in the case of Bodoland Council, where the new chief had less resonance among the Bodos, are instances where identitarian political movements are curbed by the state’s interference with the internal actors of the community (Singh & Kim, 2018; Bezbaruah, 2019). While Ambedkar’s objective for using the state forces (external) to initiate reformation within the community (internal) was to curb the graded inequality adversely impacting the ‘Untouchables,’ denying them equality and freedom, the governments have consistently and excessively used centralisation and state intervention to bring reforms within a religious community. The very recent law on the Waqf bill also indicates excessive state interventions with seemingly ambiguous motivations behind them. Another crucial aspect is Ambedkar’s emphasis on leaving a wide enough scope for the exit for both Muslims (from British India) and the “depressed classes” (from the Hindu religious community) if they feel a lack of belongingness as kith and kin. His commitment to allowing or ensuring this freedom to exist is evident in his words, “I prefer the Freedom of India to the Unity of India,” thereby indicating his conviction against force of any kind, especially on the minority community (Ambedkar, 1946, p. 367).

However, the hypothetical question worth asking for clarity is whether Ambedkar would have allowed the ‘depressed classes’ to secede and form a separate nation-state since, although sharing the same past with other Hindus, they were oppressed and subjected to inhuman treatment; further, by their renouncing Hindu religion (like Ambedkar and many more in his footsteps), the common religious link would be severed too. Finally, their sense of nationality developed and transformed into nationalism, which fulfilled the grounds for their separation as well.

Further, while a superficial glance might show Ambedkar in contradiction to Tagore, who was against the state being the centre of all socio-economic activities, the complexities pointed out by Ambedkar in the way of reform, internally within the Hindu community, offer sufficient justifications for state-led reforms. These three-pronged complexities include challenging the authority of the Brahmins, the caste system and the Hindu religious scriptures like Vedas and Shastras (Lamba, 2013). To answer the state-level interventions, it is worthwhile to note that Luis Cabrera in his paper dealing with Ambedkar as a cosmopolitan, has pointed out Ambedkar’s support for the “state-transcendent universal human rights”, which he found to be non-negotiable irrespective of culture, state membership or any other identity marker (Cabrera, 2017, p. 583). His opposition to “uncritical loyalty to the state” was pointed out with his argument that the loyalty to state should be conditional to the state’s protection of the people (Cabrera, 2017, p. 577). For Ambedkar, the state exists for the welfare of the people and has no moral significance apart from this role. Not only the state but institutions, practices, and even whole religions need to be examined and countered if they violate universal human rights. Third, he advocated appealing to international authorities in case of violation of human rights, which is usually the case with minority communities (Carbera, 2017).

Here, it is also helpful to take up the concept of ‘social endosmosis’ advocated by John Dewey, the scholar and educator who had a great influence on Ambedkar. The scientific meaning of the term is the flowing of fluid through a membrane, and Dewey has only once referred to social endosmosis by arguing in chapter seven of his book Democracy and Education, that “a separation into a privileged and subject-class prevents social endosmosis” (Dewey, 1997, p. 84). However, Ambedkar builds on it by arguing that only “a free social order” ensures social endosmosis whereby without discrimination and restrictions, all classes are able to intermingle and share interests “when there is a free play back and forth,” thereby leading to ease in mobility (Mukherjee, 2009, p. 261). The “like-mindedness” is what is underlined while drawing attention towards social endosmosis (Cabrera, 2017, p. 586). It can, therefore, be argued that Ambedkar did not oppose the claims of a separate nation for Pakistan and pointed out the flaws in the Hindu social order; his convictions on shared living remained intact. To sum up, Ambedkar’s views uphold the concern for minority rights, whether religious or caste-based, and his commitment to stand by his convictions despite backlash is worthy of recognition. In contemporary times when state surveillance, and friction between linguistic, regional and religious communities have intensified, Ambedkar’s thoughts hold immense relevance.

Conclusion

The commentary attempts to show Ambedkar’s views on nationalism and the aspect of community. It poses the question of whether Ambedkar’s views conform to the Western nationalist ideals of an ethnic nation, or they are based primarily on allowing the will of the community to be the basis of a separate nation-state. The importance of emotional valence is highlighted to show the then-growing estrangement between Hindus and Muslims, whereby Ambedkar allowed the scope of exit. In the case of intra-community dynamics, Ambedkar’s critique of the Hindu social order is highlighted, along with his justification for state-level interventions for reform and his support for the scope of exit while also arguing in favour of social endosmosis. To sum up, one needs to be cautious in labelling or categorising Ambedkar as a “nationalist” or “crusader”; instead, his political thoughts are premised on reason which needs to be viewed contextually to be able to better grasp him.

References:

Rodriguez, V. (2002). The Essential Writings of BR Ambedkar. London: Oxford University Press.

Ambedkar, B. (2017). DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 8.https://www.amazon.com/BABASAHEB-AMBEDKAR-WRITINGS-SPEECHES-VOL-ebook/dp/B074JFP225

Bhargava, R. (2000). History, nation and community: Reflections on nationalist historiography of India and Pakistan. Economic and Political Weekly, 193-200.

Bezbaruah, M. P. (2019). Cultural Sub-Nationalism in India’s North-East: An Overview. Subnational Movements in South Asia, 171-190.

Chatterjee, P. (1993). The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton University Press.

Cabrera, L. (2017). “Gandhiji, I Have no Homeland”: Cosmopolitan Insights from BR Ambedkar, India’s Anti-Caste Campaigner and Constitutional Architect. Political Studies, 65(3), 576-593.

Dewey, J. (1997). Democracy and education. Free Press.

Guru, G. (2016). Nationalism as the Framework for Dalit Self-realization. Brown J. World Aff., 23, 239.

Kaviraj, S. (2019). Tagore and the conception of critical nationalism. In Religion and Nationalism in Asia (pp. 13-31). Routledge.

Lamba, R. (2013). State Intervention in the Reform of a” Religion of Rules” An Analysis of the Views of BR Ambedkar. Secular States and Religious Diversity, 187.

Mukherjee, A. P. (2009). BR Ambedkar, John Dewey, and the meaning of democracy. New Literary History, 40(2), 345-370.

Singh, G., & Kim, H. (2018). The limits of India’s ethno-linguistic federation: Understanding the demise of Sikh nationalism. Regional & Federal Studies, 28(4), 427-445.

Thorat, S., & Kumar, N. (2008). BR Ambedkar: Perspectives on social exclusion and inclusive policies.

Caste-ing Gender: The Politics of Knowledge Production and the Call for Reflexive Feminism

Any critical engagement on the question of caste and gender must begin with acknowledging the politics of knowledge production. The politics of knowledge production involves conscious/unconscious neglect of certain sources to serve as the basis of knowledge production driven either by the desire to conform to the dominant discourses in academia or to give in to varying modes of thinking and action in the context of activism. This commentary draws attention to both these processes which directly or indirectly affect the content of feminist knowledge production on the issue of caste.

To do so, the commentary first draws on Karl Mannheim’s Sociology of Knowledge Approach to examine how knowledge is socially situated and Gopal Guru’s theorisations of how upper-caste perspectives have been historically privileged in Indian academic discourses. This results in the marginalisation of the lived experiences and intellectual contributions of Dalits, especially Dalit women as highlighted by Sharmila Rege’s work which sheds light on the ignored feminist dimension of Ambedkar’s anti-caste writings. Second, the commentary critically interrogates the fractures within feminist and anti-caste movements by analysing two major moments of selective solidarities within the feminist movement. It explores how we can engage with these moments creatively, by drawing on the works of scholars such as Susie Tharu, Tejaswini Niranjana, Nivedita Menon, and Sowjanya Tamalapakula.

Using Mannheim’s Sociology of Knowledge Approach helps us understand the social basis of knowledge. Knowledge is situated—that is, it emerges from specific social locations and cannot be entirely separated from the historical and cultural contexts in which it is produced. It is often particularising, shaped by the social position, interests, and experiences of the individuals or groups generating it. The sociology of knowledge traces practices historically over time, to understand their social origins (Mannheim, 1982).

To move beyond a tokenistic invocation of caste in academic work or movements, it is necessary to interrogate who gets to theorise and whose experiences are allowed to shape theory. ‘The Cracked Mirror’ by Gopal Guru and Sundar Sarukkai (2017) offers a powerful critique of the caste-based hierarchy of knowledge production in Indian social sciences. They draw attention to how theoretical labour has often been reserved for upper-caste scholars, while Dalits have been relegated to the domain of experience and empirical knowledge—mirroring what Guru (2002) terms the divide between “theoretical Brahmins” and “empirical Shudras.” The result is a persistent silencing of Dalit women’s voices in both feminist and anti-caste discourse.

In the context of knowledge production on caste and gender, Rege’s ‘Against the Madness of Manu: B.R Ambedkar’s Writings on Brahmanical Patriarchy’, is a small step in the direction of understanding the neglected feminist dimension in anti-caste writings of Ambedkar by non-Dalit feminists and Dalit Men (Rege, 2006). The two central themes that illuminate the gendered dimension of caste in Ambedkar’s writings are those of endogamy and exclusionary violence.

Ambedkar refers to caste as “an enclosed class”, implying that castes exist due to “the operation of the process of enclosure, either by enclosing in the case of Brahmins or by being enclosed against in the context of other castes” (Rege, 2013, 35). This enclosure is achieved primarily through the superimposition of the practice of endogamy within castes over any exogamous units of the society. The practice of endogamy stems from an attempt to control the problem of surplus women and men. The former issue is dealt with by either burning the woman with her dead husband or an imposition of widowhood. The latter, due to the superior status of men to women, do not undergo similar treatment, instead, they are provided wives from the ranks of those not yet marriageable to tie down within the group, which also results in girl child marriage. The formation of castes, thus, involves the imitation of the practice of endogamy by different castes to form an enclosed class against others (Ambedkar, 1979). Thus, Ambedkar rightly acknowledges that endogamy is the only sustaining characteristic of caste.

Rege also draws upon Ambedkar’s writings which seek to provide a comparative analysis between the experiences of women guided by the principles of Manu, and his teachings/interaction with Buddhism. It is through this comparison, that Ambedkar sought to highlight the exclusionary, discriminatory, and violent nature of Manu. The Manusmriti relegated women to an inferior and subordinate status in Hindu society. It portrayed women as inherently seductive, untrustworthy, and intellectually and morally weak. It prescribed to the husbands of all castes to strive to guard their wives, and by extension, impose restrictions and subject them to various forms of violence to achieve the same. Women were denied independence in every stage of life—subject to the authority of their fathers, husbands, and sons—and were stripped of property rights, education, religious agency, and even the right to divorce. Manu not only justified corporal punishment against women but also allowed men to abandon or even sell their wives without granting them the same liberty. By reducing women to near-slaves, devoid of autonomy, knowledge, or legal personhood, Manu codified a vision of social order that institutionalised gender-based subjugation and normalised violence and inequality against women. Ambedkar viewed the conversion of Manu into the law of the state as an important factor contributing to the fall of Hindu Women, the principles of which had always otherwise existed as a social theory (Ambedkar, 2003).

Moving ahead to the second part of our discussion on the issue of politics of knowledge production, one must draw attention to the fact that just like Ambedkar attributed the deplorable conditions of women in different castes to the process of imitation, many non-Dalit feminists conceptualise Dalit patriarchy as an extension or imitation of Brahmanical patriarchy.

The politics of knowledge production also play out in the field of activism, where activists employ varied modes of thinking and action depending on the context and larger commitments of the movement. In ‘Problems for a Contemporary Theory of Gender’, Tharu and Niranjana draw attention to two important instances – middle-class/upper-caste feminist participation in anti-Mandal agitation and the Chunduru incident which resulted in the murder of thirteen Dalits by upper-caste Reddys on the ground of accusations of eve-teasing of the upper-caste women by the Dalit men. In the case of the former, the commitment of the non-Dalit feminist movement is brought into question on the grounds of ignoring the nuances of other violent structures like the caste system and its interaction with patriarchy in favour of class-based solidarity in the face of the implementation of reservations (Tharu & Niranjana, 1994). In the context of the latter, feminist condemnation of Dalit men’s conduct in Chunduru in the background of the long history of sexual violence committed by the upper caste men against Dalit women revealed the fractures within the feminist movement in terms of the symbolic and actual commitment to the ideals of intersectionality. Both these instances are typical of moments within the feminist movement where the dominant understanding of the ‘feminist’ subject has been brought to question in the context of a rapidly globalising economy that disables alliances between feminists and other movements (caste movements in this context).

Menon (2009) suggests that both Dalit and feminist politics must destabilise each other in different contexts in order to complicate the landscapes of thinking about critical issues that involve gendered violence in a caste-based society. She advises against the fruitless debate regarding which forms the primary contradiction – whether it is caste or gender – which seeks to solidify boundaries between the two, instead of productively opening them up to critically engage with the challenge and criticism provided by the Dalit and non-upper caste feminists.

A particular step in this direction can be seen to be taken by Sowjanya in her paper titled ‘Dalits and Inter-caste Marriage’ where she critiques the traditional perspectives on endogamy, such as Ambedkar’s view of putting into motion the process of annihilation of caste by encouraging inter-caste marriage. While not completely disagreeing with Ambedkar’s proposed solution, Sowjanya highlights the politics around present-day inter-caste marriages. She asserts that contemporary Dalit ideology promotes inter-caste marriage to subvert caste endogamy, a central tenet of Hindu society. But not all inter-caste marriages are in the spirit of Ambedkar’s views expressed in ‘Annihilation of Caste’. While many Dalit ideologues and educated Dalit men promote and practice inter-caste marriage, Dalit women, on the other hand, have voiced their experiences of untouchability and caste discrimination after being married to upper-caste men (Sowjanya 2015). She argues that inter-caste marriages, rather than dismantling caste structures, often reinforce caste hierarchies through gendered oppression and exclusion.

The commentary aims to contribute to the project of epistemic justice by interrogating who gets to produce knowledge and whose voices are validated in the domain of academic knowledge production as well as in movements for social change. By highlighting Rege’s attempt to explore the feminist dimension of Ambedkar’s writings, Menon’s call to destabilise Dalit and feminist politics in different contexts, and Sowjanya’s critique of inter-caste marriage as a site of continued caste and gender-based exclusions, the commentary opens up the space for more inclusive and reflexive forms of theorising gender by being sensitive to the dimension of caste in the Indian society.

REFERENCES

Ambedkar, B. R. 1979. Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development. In BAWS, Vol. 1, 5–22. Mumbai: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra. (Originally published in Indian Antiquary 41 (3): 81–95).

Ambedkar, B. R. 2003. The Rise and Fall of the Hindu Woman: Who Was Responsible for It? In BAWS, Vol. 17, Pt. 2, Sec. 4, 109–130. Mumbai: Government of Maharashtra, Education Department. (Originally published in Maha Bodhi 59 (5–6)).

Gopal, Guru. 2002. “How Egalitarian Are the Social Sciences in India?” Economic and Political Weekly 37 (50): 5003–5009. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4412959.

Guru, Gopal, and Sundar Sarukkai. 2017. The Cracked Mirror: An Indian Debate on Experience and Theory. Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Mannheim, Karl. 1982. The Sociology of Knowledge. In The Sociology of Knowledge: A Reader, edited by J. E. Curtis and J. W. Petras, 109–130. London: Gerald Duckworth and Co.

Menon, Nivedita. 2009. “Sexuality, Caste, Governmentality: Contests over ‘Gender’ in India.” Feminist Review 91: 94–112. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.2008.46.

Rege, Sharmila. 2013. Against the Madness of Manu: B. R. Ambedkar’s Writings on Brahmanical Patriarchy. New Delhi: Navayana.

Tamalapakula, Sowjanya. 2015. “Dalits and Inter-Caste Marriage.” Academia.edu, September 18. https://www.academia.edu/15840725/Dalits_and_Inter_caste_Marriage.

Tharu, Susie, and Tejaswini Niranjana. 1994. “Problems for a Contemporary Theory of Gender.” Social Scientist 22 (3/4): 93–117. https://doi.org/10.2307/3517624.

Between Blue and Saffron: Revisiting Ambedkar and the contradictions of Indian democracy today-I

A couple of years ago, in the month of April 2018, a statue of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, one of the founding fathers of India’s constitutional democracy, was vandalised in a village, Badaun, in Uttar Pradesh. The statue was reinstated the following week and painted in saffron. This was unusual, as Ambedkar is usually associated with the colour blue or sometimes black. After public outrage, a Bahujan Samajwadi Party worker repainted it blue. The makeover of Ambedkar from blue to saffron to blue is representative of the tussle over his iconography. Dr B. R. Ambedkar, in recent months, has saturated the Indian political imagination in the most interesting ways, pulling him in varied directions—left, right, and centre. Babasaheb’s ideas and thoughts continue to be revisited as different political groups claim him for their own ideological purposes. While one hails him as the messiah of Dalits and the father of the Indian Constitution, the other positions him as a faithful patriot to the nation. Ambedkar today stands between blue and saffron.

(Image Source: OnManorama, 2018)

The resilience of his legacy is exemplified in his reimagining as a leader speaking from and to the margins, alone as a universal icon—familiar, yet a little too enigmatic to be contained within the complex identitarian categories of Indian politics. His greatest offering to the Indian nation—the Constitution—has stood the test of time and continues to evolve as a document. In more recent times, the political symbolism of the Indian Constitution, used to pose an effective counter-narrative to the Hindu right-wing forces, has sacredly tethered the unbridled potential of an ‘idea of India’ with a collective political action that revitalises newer formations of ‘the people’. Ironically enough, in times of constant misuse and abuse of the Constitution, instead of burning it—as Ambedkar would have had it—the document has garnered a mystical power of its own. Preamble reading and public demonstrations of the Constitution have assumed a new performative meaning that ritualises the spirit of solidarity among sections of the population, bringing them together to achieve a common good. The Constitution has become, as Ambedkar believed, ‘a vehicle of life’ and a ‘spirit’ of this age. However, as this decade has witnessed the systematic decimation of the Nehruvian state and its ideological sway, it is imperative to ask: How did we get here? How did one of the largest democracies in the world slip into the abyss of majoritarianism? Were there predispositions for such authoritarian tendencies present since the inception of India’s democracy?

Growing Hindu majoritarian sentiments are a major blow to caste discourse, which is deliberately erased to propagate the political rhetoric of ‘Hindu unity’. Moreover, caste-based regional parties are struggling to counter the offensive march of the Bharatiya Janata Party—a party committed to the Hindutva ideology that refurbishes caste hierarchies, yet also claims to have done the most for the upliftment of Dalits and worships Ambedkar.

The Hindu right-wing does not merely aim to win elections; rather, it seeks to transform Indian society and culture into its own vision of a nation. The current life of Indian democracy is marked by a resurgence of communal registers of politics, indicating a disenchantment with secularism. Questions of caste and reform have either been swept under the carpet in the name of Hindu unity or face attacks on welfare politics itself. The fate of democracy is such that the government skirts around any deliberation on deepening socio-economic inequalities and has coercively crushed any democratic movements by marginalised groups. It is also true, however, that the latter have also failed to sustain inter-group solidarity to pose an effective counter-movement to the Hindu right. Thus, in the face of already decaying institutions and the declining health of the body politic, how do we reimagine and recalibrate the political imagination of the nation?

In a desperate search for political alternatives and a sustainable way out of the current political conundrum, this paper turns to Ambedkar’s insightful understanding of Indian society and politics. This paper recalls Ambedkar’s warning at the altar of India’s independence for the purpose of addressing the contradictions of democracy today:

“On the 26th of January 1950, we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics we will have equality, and in social and economic life we will have inequality. In politics we will be recognizing the principle of one man one vote and one vote one value. In our social and economic life, we shall, by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to deny the principle of one man one value… How long shall we continue to live this life of contradictions? How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life?If we continue to deny it for long, we will do so only by putting our political democracy in peril. We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment or else those who suffer from inequality will blow up the structure of political democracy which this Assembly has so laboriously built up.” – (Dr B.R Ambedkar, Constitution Assembly, 26th January, 1950)

This paper aims to provide an Ambedkarite remedy to the contradictions of Indian democracy in three interrelated measures: (i) the intricate relationship between the social and political, (ii) the reconceptualisation of democracy as ‘associated living’ as opposed to its conception as the rule of the majority, and (iii) communal questions and the ‘de-binarising’ the Hindu-Muslim debate. The paper puts forth two preliminary arguments for discussion. First, the surge of the Hindu right is not a ‘break’ from liberal democracy as usual; rather, it is only an aggressive byproduct of a troubled relationship between the social and political. Second, the Hindu-Muslim ordering of Indian secularism since the Partition and the contemporary hardening of the binaries obfuscates the socio-political realities of Indian society and politics. This paper problematises the stand of both liberal and right-wing political imaginations of Indian history as that of religious strife and contention. It revisits Ambedkar’s prominent works, particularly Annihilation of Caste, Pakistan or the Partition of India, and some of his other works and speeches.

Lastly, the urgency of writing this paper stems from a gnawing awareness of the appropriation of Ambedkar by the Hindu right in repurposing his anti-caste vision, devoid of its radical content, to articulate their Hindutva ideology. This essay comes as a wake-up call to the progressive camps regarding the Right’s absorption of Ambedkar into their ‘Hindu pantheon’, albeit it seems contradictory given the icon’s popular reputation as a critic of the Brahmanical order. However, one can no longer afford to be deluded by the seductive appeals of the Right, or we might not stand a chance to retain Ambedkar’s quintessential vision for action. This paper is divided into two parts: the first part by Aneri Vora is titled “Interweaving the Social and the Political: Ambedkar’s Compelling Vision for Socio-Political Emancipation.” The second essay by Sanjana, titled “Revisiting Ambedkar in the Times of Crisis: Rescuing Indian Democracy from the Hindu Right,” highlights Ambedkar’s views on the communal question and hinges the Hindu-Muslim relationship on caste. It argues that the Hindutva movement—and the counter to it—has phased out caste concerns. This paper makes a case for caste-inclusive transformative politics through an earnest acknowledgment of intersectionalities while forming solidarities. This will facilitate common goals and build trust, thereby creating spaces for mutuality and alliances in a deeply fractured society.

This two-part essay is a poignant ode to the everyday struggles of Dalits, Muslims, and women who have remained at the margins of democratic discourse that has been occupied by a handful of political elites, then and now.

I

The Contradictions between the Social and the Political: Locating Ambedkar between Tradition and Modernity

An important factor behind the rise and popularity of right-wing politics in India is its recognition of the importance that culture, folk idioms, and everyday practices—including moral and ethical codes of conduct based on them—hold in the self-understanding and perceptions of the electorate (Gudavarthy, 2023). The BJP draws its ideological moorings and narrative power from its overarching goal of consolidating and strengthening Hindu religion and culture, which would form the basis of the Indian nation-state. This is foremost a social project, as cultivating a Hindutva identity involves homogenising and foregrounding certain Hindu rituals and socio-cultural practices (viz. the BJP’s temple politics, emphasis on a glorious Hindu past and a golden age of Hindu history, valorising indigenous i.e. Hindu traditions and knowledge, tapping into popular sentiments of ‘pseudo-secularism’ and the ‘Muslim threat’, among others).

The BJP and its allied organisations thus prioritise the social over the political, where the state and its agencies are subservient to the larger ideological goal of securing an ethno-religiously homogeneous Hindu nation and society. The state, then, is merely a means to facilitate the societal and cultural transformation required by the Hindutva project. In line with this, the right wing has had a long history of grassroots organising and mobilisation, including civil society and non-governmental organisations that spread its message of unity (cultural, religious, and political), pride, martial discipline, and a strong sense of belonging (Andersen and Damle, 2019). This emphasis on the social over the political is unlike that of the centrist and left parties, whose orientation and leadership in recent decades have largely been top-down and elitist, which has been an important factor in their inability to capture political imagination or offer a viable political alternative.

This divide between the social and the political is also evident among the leaders of post-independent India, where leaders of the Left and Congress focused their energies on the state and its laws and institutions as the main foci of social change. Thus, not only was Nehru preoccupied with the question of how to bridge the gap between his elite social location and the lifeworld of the masses, his faith in science, technology and modernisation also led him to believe that caste, religion, and gender-based issues would be resolved through top-down modernisation and state-led policies (Parekh, 1991; Bilgrami, 1998). Similarly, the Left’s economic determinism, discomfort with socio-cultural and religious questions, and the elite locations of many of their top leaders led to a neglect of the social.

Apart from the Hindutva movement, whose emphasis on culture and tradition was largely exclusionary and status quoist, Gandhi was among the few who recognised the importance of speaking in the popular idiom and crafting a politics that draws from cultural and folk elements, using the same for his emancipatory project. However, his politico-economic programme of a polity based on autonomous villages with local self-government, economic self-sufficiency, and opposition to large-scale industrialisation was largely seen to be unviable and impractical in a world where growth and development had become synonymous with modernisation and industrialisation. While Gandhi’s programme was indeed a radical philosophical critique and rejection of the pathologies of Western civilisation, Indian leaders had much more immediate and practical concerns such as poverty alleviation, provision of basic social services such as food, housing, education and healthcare, and the development of agriculture and industry to ensure self-sufficiency in food and industrial production, among other things. Not only was economic growth and development important to achieve these aims, India also had to take its place in a world where modernity and industrialisation had become a way of life and the norm of governance, leading to a reorganisation of the international economy and the international politics of aid—especially at a time when India had been ravaged by systematic loot, deindustrialisation, pauperisation, and impoverishment due to colonial misgovernance and policies.

Gandhi’s socio-cultural project, on the other hand, while drawing on a capacious and creative reinterpretation of Hinduism and ethical self-transformation through Swaraj, Ahimsa and self-suffering, also emphasised the importance of communal harmony and religious tolerance as deeply embedded in the socio-historical fabric of India. Despite this, his vision did not outline a programme for structural criticism and change, where a radical and revolutionary praxis could attack and alter existing inequalities based on caste, gender, religion, region, and sexuality. Gandhi’s ambiguity regarding the Chaturvarna system has led to fierce debates among scholars (Dalton, 1995; Pantham, 1983; & Biswas, 2018), and his emphasis on ‘virtuous womanhood’ (Binu, 2023) shows how his vision retained elements of conservatism, falling short of radical socio-political transformation.

The discussion so far indicates a fundamental tension between programmes that draw from popular morality and cultural idioms on the one hand, and those advocating for a radical praxis for the liberation of the vulnerable and historically underrepresented groups on the other. While the former are able to better connect with the masses, they often fall prey to varying degrees of conservatism; while the latter, although conducive to modernity with an emphasis on equality and dignity for all, envisage a top-down process of change and transformation, where the masses obediently follow in the footsteps of the enlightened elite. In this context, Dr Ambedkar’s socio-political philosophy emerges as an attractive alternative.

A firm believer in the values underlying modernity and the Enlightenment, Ambedkar placed a premium on the latter’s motto of liberty, equality and fraternity. In his lifelong crusade against the rigidly hierarchical caste system and fierce criticism of ubiquitous caste-based discrimination, Ambedkar argued for the importance of cultivating the ability to think rationally and critically for oneself. Having experienced caste-based discrimination himself, Ambedkar recognised the necessity of overthrowing exploitative social structures and radically reinventing practices, customs and ways of living that oppressed individuals and groups based on ascriptive identity markers like caste, gender, religion and class. Recognising how caste-based hierarchies and practices of untouchability (among other oppressive structures and practices) gain legitimacy and permanence in the name of religious dictates and cultural pride deriving from tradition—such as sacred religious books and scriptures—Ambedkar presciently forewarned us of the dangers of blind obedience and deference to authority. For caste Hindus, rational and critical thinking would lead to a recognition not simply of the futility and irrationality of the caste system, but also of the grave moral injustice and ethical injury that the caste system represents. The existence of caste not only exposes as farcical the claims to superiority and glory of Indian civilisation and tradition but also calls for an absolute and radical ‘reconstruction’ of Hinduism where the caste system is destroyed in its entirety. Ambedkar became increasingly doubtful of the possibility of dislodging the Chaturvarna system as one of the central tenets of Hinduism, eventually converting to Buddhism on 14th October 1956.

The lower castes and Dalits, on the other hand, needed to recognise their self-worth, self-respect and dignity, boldly raise their voices against caste-based discrimination and unite in their struggle in demanding recognition of their personhood, equal human rights and opportunities, equitable material redistribution, and redressal of the sub-human treatment meted out to them for centuries. The highly popular slogan ‘Educate, Agitate and Organise’ embodies the importance Ambedkar placed on Western education and on cultivating a rational, modern outlook for the Dalits to reclaim their rightful place in Indian society and the dynamic, modern world beyond. As a national icon, Ambedkar is often represented in his trademark three-piece blue suit, armed with a book in hand. In the commonly practised politics of symbolic representation, images of iconic national leaders—through their content, source and mode of representation—come to represent competing ideas of the nation, national belonging and community, signify attempts at appropriation, and serve as important tools in struggles for meaning-making and power. In this context, Ambedkar’s representation in a blue suit, book in hand, which has been circulated, used and popularised by the Dalit community, serves as a “symbol of aspiration and striving” for the community (Kumar, 2017), based on a modern sensibility.

Given his emphasis on reason, rights, individual dignity, self-determination and autonomy, Ambedkar recognised the importance of formal law and constitutional safeguards in institutionalising and realising these normative ethical ideals in reality. Apart from his seminal contributions as the Chairman of the Drafting Committee and the first Law Minister of the country, Ambedkar was also a proponent of parliamentary democracy, contesting a national election and a by-election in 1952 and 1954 respectively, as a candidate from the Scheduled Caste Federation (a political party he founded). However, despite being a national leader, a high-ranking minister and a revered figure of socio-political emancipation, Ambedkar was never able to win an election. Thus, despite attaining high-ranking political positions and stature, Ambedkar was unable to secure broad social support for his project of a systematic and structural critique of caste Hindu society and the establishment of an open, casteless society in its wake. Similarly, despite attaining multiple higher education degrees from elite institutions abroad, Ambedkar had trouble finding housing upon his return to India.

This contradiction between the social and the political, between cultural norms and formal institutions, was a contradiction that Ambedkar had to grapple with throughout his life. Perhaps this was also the reason why Ambedkar was acutely aware that political change cannot occur without social change, and that social reform was perhaps more, if not as, important as political reform. His awareness of the importance of addressing cultural and religious practices, rituals and traditions is perhaps nowhere more evident than in his book The Annihilation of Caste. Originally meant as a speech to be delivered at the Jat-Pat Todak Mandal (a radical wing of the Arya Samaj), Ambedkar was eventually forced to self-publish 1,500 copies of this speech.

Notwithstanding the iconic status it has since attained, the most important aspects of the speech for our purposes are Ambedkar’s recognition of how the social realm has been ignored in favour of the political, and his emphasis on the indispensability of radical social and religious change, without which deep-rooted emancipatory possibilities cannot be realised. The speech initially begins with a note on the battle between the social and political organisations of the Indian National Congress, which, as Ambedkar notes, the social wing decisively lost. Ambedkar argues that the social wing lost because they mainly focused on reforms within the high-caste Hindu family, rather than advocating for the abolition of the caste system itself. To quote Ambedkar:

“It also helps us to understand how limited was the victory which the ‘political reform party’ obtained over the ‘social reform party’… that political reform cannot with impunity take precedence over social reform in the sense of the reconstruction of society, is a thesis which I am sure cannot be controverted” (Ambedkar 1936, sec. 2.16).

Ambedkar notes further:

“To sum up, let political reformers turn in any direction they like, they will find that in the making of a constitution, they cannot ignore the problem arising out of the prevailing social order” (Ambedkar 1936, sec. 2.16).

This keen awareness of the intricate relationship between the social and the political, and their repercussions in democratic life, makes Ambedkar truly unique. The caste question not only found considerable space in his political thought, but it was also complemented with a political programme.

Interweaving the Social and the Political: Ambedkar’s Compelling Vision for Socio-political Emancipation

Contesting the materialism and class primacy of Marxists and socialists, Ambedkar argues that it is religion that touches the human soul most deeply and motivates human behaviour (Ambedkar 1936). In a caste-riddled society like ours, a proletarian revolution will not abolish the caste system. Criticizing the views of those who argue that caste allows for economic efficiency or racial purity, Ambedkar notes that caste has only served to weaken and divide Hindu society. In fact, he argues that “Hindu society is a myth” (Ambedkar 1936, sec. 6.2), consisting “only (of) a collection of castes” (Ambedkar 1936, sec. 6.2). Outlining his own conception of an ideal society, he argues that mere similarity of customs, habits, beliefs and thoughts do not constitute a society. Static and closed societies where groups simply copy each other cannot be a nation/society in the true sense. As Ambedkar notes,“Men constitute a society when they possess things in common,” which is different from “having things in common” (Ambedkar 1936, sec. 6.6). The former, Ambedkar’s desired society, is a dynamic and open society where men come to possess things in common through active and constant communication. Men must “share and participate in a common activity, so that the same emotions are aroused in him that animate others” (Ambedkar 1936, sec. 6.7). This, Ambedkar refers to as the “associational mode of living”, where communities are marked by a spirit of solidarity and belonging that derives from regarding every member as an equal and as partners in a shared destiny. “Making the individual a sharer or partner in the associated activity, so that he feels its success as his success, its failure as his failure, is the real thing that binds men and makes a society of them” (Ambedkar 1936, sec. 6.7). While other communities such as the Sikhs, Muslims and Christians share such associational modes of living, the caste system prevents Hindus from doing so. The point here is not that each religious or ethnic group should have their own modes of associational living; Ambedkar rather wants to recover the impulse towards acknowledging the radical equality inherent in each individual that these religious groups recognise, which in turn serves as the glue that binds society together in a spirit of brotherhood.

For Ambedkar, there is a close connection between the society and the nation, and he often uses them synonymously. Both require an associated mode of living, based on a sense of belonging cultivated on values of equality, brotherhood and love, which a stratified caste-based society is unable to foster. Ambedkar’s conceptions of nation and society are then tied to his conception of the polity, which is far deeper than an emphasis on parliamentary democracy and human rights. It consists of what Scott Stroud has described as a pragmatic conception of democracy (Stroud, 2023a). This is a dynamic and vibrant conception of democracy where each of us puts forth our views and defends our conceptions of the good, while also remaining open to those we disagree with. Liberty, equality and fraternity for Ambedkar served as semi-transcendent ideals (Stroud, 2023b) that are neither metaphysical commands nor timeless natural rules, nor are they entirely relative, arising wholly from our community and social practices—lying somewhere in between instead. Each of these values represents separate and sometimes complementary, sometimes conflicting ideals that we fine-tune and try to bring into balance through a community based on equality and open communication with each other.

Such a society “should be mobile, should be full of channels for conveying a change taking place in one part to other parts… There should be varied and free points of contact with other modes of association. In other words, there must be social endosmosis. This is fraternity, which is only another name for democracy. Democracy is not merely a form of government. It is primarily a mode of associated living, of conjoint communicated experience” (Ambedkar 1936, sec. 14.2).

As we shall see in the second part of this article, the right wing has often used Ambedkar’s arguments on the communal question and his views on the caste system as an impediment to socio-political unity, to appropriate his thought. In arguing for the abolition of the caste system, Ambedkar often emphasised how the fragmentation and division of Hindu society along caste lines prevented a consolidated Hindu society and nation from emerging. Savarkar’s anti-caste crusade and Ambedkar’s appreciation of the former have also been used to appropriate Ambedkar. However, not only did Savarkar, as president of the Hindu Mahasabha, ensure that his anti-caste activism remained strictly separate from the Mahasabha, Ambedkar’s criticism of Savarkar for his advocacy of retaining a modified Chaturvarna system is also conveniently ignored (Islam, 2023). Ambedkar was also against the creation of a nation-state based on religious and cultural majoritarianism, advocating instead for a polity grounded in an open, dynamic and participatory society.

Moreover, in presenting him as an advocate of a homogeneous majoritarian ethno-cultural conception of nationalism, they inevitably erase the fundamental tensions between Ambedkar and the then Hindu right wing. This tension is manifest in the Jat-Pat Todak Samaj’s revocation of the invitation it had extended to Ambedkar since the latter’s speech “called for a complete annihilation of Hindu religion, doubted the morality of the sacred book of the Hindus as well as hinted at Ambedkar’s intention to leave the Hindu fold” (Gautam, 2022). After Ambedkar’s refusal to even “alter a comma” (Gautam, 2022), the Mandal withdrew its invitation.

Ambedkar’s scathing critique of Brahminical Hinduism has always been a point of tension between him and the right, which the latter refuses to acknowledge. After systematically decimating all arguments that advocate for a continued or reformed existence of the Chaturvarna, Ambedkar locates its source in the fact that caste is regarded as a sacred tenet among Hindus, which he locates in the Shastras. To quote Ambedkar, apart from inter-dining and inter-marriage, “The real remedy is to destroy the belief in the sanctity of the shastras” (Ambedkar 1936, sec.20.9). Ambedkar also criticised the institution of priesthood, calling for a radical change in the way priesthood as a profession is organised, making it democratic and meritocratic. Ultimately, it is the Brahmins who must give up their caste privileges, given that they are the vanguards of political and economic reform. However, Ambedkar does not see either the secular or the religious Brahmin leading a movement that destroys their power and privilege.

Ambedkar ultimately came to the realisation that the destruction of the caste system required stepping outside the Hindu fold and converting to Buddhism, a decision he made after carefully scrutinising other religious teachings for more than a decade. Contrary to the right wing’s assertion that Ambedkar chose Buddhism due to its affinity to Hinduism, Ambedkar recognised instead the importance of speaking to the people in their language, of framing his emancipatory project in terms they could comprehend and connect with. Buddhism, with its origins and initial growth in the Indian subcontinent, was suited to do so. More importantly, as Christopher Queen has noted, Ambedkar saw Buddhism as the religion that “met his complex requirements of reason, morality and justice” (Roychowdhury, 2017). He interpreted Buddhism as meeting “one of the most basic requirements of modernity – the exercise of individual choice, based on reason and historical consciousness” (Roychowdhury, 2017).

Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism highlights his awareness of the power of religion in defining our worldviews and self-conceptions, and therefore the importance of tapping into the social. While being a firm believer in the values underlying the Enlightenment and modernity, Ambedkar was an equally firm critic of British colonialism and imperialism, while also recognising the importance of ensuring that his discourse resonates with the everyday understanding of the masses. His Buddha and His Dhamma, argue Rathore and Verma (Ambedkar 2012), represents an ingenious attempt to develop a political theology that serves as a liberatory philosophy and practice for oppressed groups, grounded in ethics and morality based on universal respect, equality and compassion. They quote Bellwinkel and Schempp (2004), who argue, “Dr Ambedkar was, through the example of Hinduism and the caste system, painfully aware of the entanglement of religion and society; therefore, he intended to reconstruct Buddhism not only as a religion for the untouchables but as a humanist and social religion, which combined scientific understanding with universal truth” (Bellwinkel and Schempp, 2004, in Rathore and Verma, 2012, p. 15). Apart from reinterpreting Liberty, Equality and Fraternity through a Buddhist lens, The Buddha and His Dhamma also includes a host of ethico-political concepts that serve as the basis for a community based on radical equality, freedom and solidarity. Among other virtues such as sila, which means fear of doing wrong, khanti, which is forbearance, and karuna, which implies “loving kindness to human beings”, Ambedkar also includes maitri, which signifies “extending fellow feeling to all beings, not only to one who is a friend, but also to one who is a foe; not only to man, but to all living beings” (Ambedkar 2012, p. 78). Scholars such as Chandan Gowda and Aishwary Kumar have shown how the ideal of maitri exceeds current meanings of friendship, love, compassion and belonging. As Kumar notes, a defining feature of maitri is refusing the “foundational distinction between friend and foe” (Kumar 2013). It alludes neither to friendship nor fraternity but to “adoration, an immeasurable gift of belief and compassion across the abyss of difference” that we extend even to our enemies (Kumar 2013).

Chandan Gowda (2023) notes how maitri can serve as a powerful basis for social and political community, as an unconditional extension of mutual respect, acknowledgement and a sense of camaraderie to all without fail. This extension of fellow-feeling to all sentient beings—be it the king or the bandit, the human or the animal—is a logical extension of Ambedkar’s attempt to ground democracy and society on the basis of a radical conception of equality, which recognises the unconditional value and dignity of life itself. This then ties into Ambedkar’s emphasis on maitri as a life-giving force in contrast to modern conceptions of sovereignty, which regard the modern state’s most important feature as its power to punish, its monopoly on legitimate force and violence, and to take human life.

Quoting Ambedkar, Gowda (2023) notes: “Could anything other than maitri, he (Ambedkar) asks, ‘give to all living beings the same happiness which one seeks for one’s own self, to keep the mind impartial, open to all, with affection for everyone and hatred for none?’” As Gowda (2023) further points out, in his posthumous work Riddles of Hinduism, Ambedkar comes to ground the concepts of liberty, equality and fraternity in the Buddhist religion, and liberty and equality were sustained not by law but by fellow-feeling. This fellow-feeling was now represented not by fraternity but by maitri. “Departing from a human-centred idea of community, maitri gestures to the sentient world at large and fosters an expansive political consciousness where nation, religion, race, caste, gender and language, among other sources of social identity, do not come in the way of experiencing community life freely and vastly. The male-centred image of brotherhood implied by fraternity also makes way for a wider sense of solidarity encompassing human as well as non-human life” (Gowda 2023).