by Sanjana K.S and Aneri Vora

A couple of years ago, in the month of April 2018, a statue of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, one of the founding fathers of India’s constitutional democracy, was vandalised in a village, Badaun, in Uttar Pradesh. The statue was reinstated the following week and painted in saffron. This was unusual, as Ambedkar is usually associated with the colour blue or sometimes black. After public outrage, a Bahujan Samajwadi Party worker repainted it blue. The makeover of Ambedkar from blue to saffron to blue is representative of the tussle over his iconography. Dr B. R. Ambedkar, in recent months, has saturated the Indian political imagination in the most interesting ways, pulling him in varied directions—left, right, and centre. Babasaheb’s ideas and thoughts continue to be revisited as different political groups claim him for their own ideological purposes. While one hails him as the messiah of Dalits and the father of the Indian Constitution, the other positions him as a faithful patriot to the nation. Ambedkar today stands between blue and saffron.

(Image Source: OnManorama, 2018)

The resilience of his legacy is exemplified in his reimagining as a leader speaking from and to the margins, alone as a universal icon—familiar, yet a little too enigmatic to be contained within the complex identitarian categories of Indian politics. His greatest offering to the Indian nation—the Constitution—has stood the test of time and continues to evolve as a document. In more recent times, the political symbolism of the Indian Constitution, used to pose an effective counter-narrative to the Hindu right-wing forces, has sacredly tethered the unbridled potential of an ‘idea of India’ with a collective political action that revitalises newer formations of ‘the people’. Ironically enough, in times of constant misuse and abuse of the Constitution, instead of burning it—as Ambedkar would have had it—the document has garnered a mystical power of its own. Preamble reading and public demonstrations of the Constitution have assumed a new performative meaning that ritualises the spirit of solidarity among sections of the population, bringing them together to achieve a common good. The Constitution has become, as Ambedkar believed, ‘a vehicle of life’ and a ‘spirit’ of this age. However, as this decade has witnessed the systematic decimation of the Nehruvian state and its ideological sway, it is imperative to ask: How did we get here? How did one of the largest democracies in the world slip into the abyss of majoritarianism? Were there predispositions for such authoritarian tendencies present since the inception of India’s democracy?

Growing Hindu majoritarian sentiments are a major blow to caste discourse, which is deliberately erased to propagate the political rhetoric of ‘Hindu unity’. Moreover, caste-based regional parties are struggling to counter the offensive march of the Bharatiya Janata Party—a party committed to the Hindutva ideology that refurbishes caste hierarchies, yet also claims to have done the most for the upliftment of Dalits and worships Ambedkar.

The Hindu right-wing does not merely aim to win elections; rather, it seeks to transform Indian society and culture into its own vision of a nation. The current life of Indian democracy is marked by a resurgence of communal registers of politics, indicating a disenchantment with secularism. Questions of caste and reform have either been swept under the carpet in the name of Hindu unity or face attacks on welfare politics itself. The fate of democracy is such that the government skirts around any deliberation on deepening socio-economic inequalities and has coercively crushed any democratic movements by marginalised groups. It is also true, however, that the latter have also failed to sustain inter-group solidarity to pose an effective counter-movement to the Hindu right. Thus, in the face of already decaying institutions and the declining health of the body politic, how do we reimagine and recalibrate the political imagination of the nation?

In a desperate search for political alternatives and a sustainable way out of the current political conundrum, this paper turns to Ambedkar’s insightful understanding of Indian society and politics. This paper recalls Ambedkar’s warning at the altar of India’s independence for the purpose of addressing the contradictions of democracy today:

“On the 26th of January 1950, we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics we will have equality, and in social and economic life we will have inequality. In politics we will be recognizing the principle of one man one vote and one vote one value. In our social and economic life, we shall, by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to deny the principle of one man one value… How long shall we continue to live this life of contradictions? How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life? If we continue to deny it for long, we will do so only by putting our political democracy in peril. We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment or else those who suffer from inequality will blow up the structure of political democracy which this Assembly has so laboriously built up.”

-(Dr B.R Ambedkar, Constitution Assembly, 26th January, 1950)

This paper aims to provide an Ambedkarite remedy to the contradictions of Indian democracy in three interrelated measures: (i) the intricate relationship between the social and political, (ii) the reconceptualisation of democracy as ‘associated living’ as opposed to its conception as the rule of the majority, and (iii) communal questions and the ‘de-binarising’ the Hindu-Muslim debate. The paper puts forth two preliminary arguments for discussion. First, the surge of the Hindu right is not a ‘break’ from liberal democracy as usual; rather, it is only an aggressive byproduct of a troubled relationship between the social and political. Second, the Hindu-Muslim ordering of Indian secularism since the Partition and the contemporary hardening of the binaries obfuscates the socio-political realities of Indian society and politics. This paper problematises the stand of both liberal and right-wing political imaginations of Indian history as that of religious strife and contention. It revisits Ambedkar’s prominent works, particularly Annihilation of Caste, Pakistan or the Partition of India, and some of his other works and speeches.

Lastly, the urgency of writing this paper stems from a gnawing awareness of the appropriation of Ambedkar by the Hindu right in repurposing his anti-caste vision, devoid of its radical content, to articulate their Hindutva ideology. This essay comes as a wake-up call to the progressive camps regarding the Right’s absorption of Ambedkar into their ‘Hindu pantheon’, albeit it seems contradictory given the icon’s popular reputation as a critic of the Brahmanical order. However, one can no longer afford to be deluded by the seductive appeals of the Right, or we might not stand a chance to retain Ambedkar’s quintessential vision for action. This paper is divided into two parts: the first part by Aneri Vora is titled “Interweaving the Social and the Political: Ambedkar’s Compelling Vision for Socio-Political Emancipation.” The second essay by Sanjana, titled “Revisiting Ambedkar in the Times of Crisis: Rescuing Indian Democracy from the Hindu Right,” highlights Ambedkar’s views on the communal question and hinges the Hindu-Muslim relationship on caste. It argues that the Hindutva movement—and the counter to it—has phased out caste concerns. This paper makes a case for caste-inclusive transformative politics through an earnest acknowledgment of intersectionalities while forming solidarities. This will facilitate common goals and build trust, thereby creating spaces for mutuality and alliances in a deeply fractured society.

This two-part essay is a poignant ode to the everyday struggles of Dalits, Muslims, and women who have remained at the margins of democratic discourse that has been occupied by a handful of political elites, then and now.

II

Revisiting Ambedkar in the times of crisis: Rescuing Indian Democracy from the Hindu Right

By Sanjana K.S.

The previous part of the paper underlined two themes in Ambedkar’s political thought: the intertwinement of the social and the political and the value of associational living through the Buddhist concept of maitri. Ambedkar understood the role of the state in empowering the deprived sections of the society for which the social had to be prioritised along with political development. Ambedkar’s deeply pragmatic and philosophical approach was rooted in his lived experience as a Dalit. He understood that the social in India had to be regulated by a modern democratic state that nurtured liberty, equality and fraternity as core values. Democracy was antithetical to the inequalities codified by the caste system. Hence, the modern state was to act as a tool of social justice and annihilate caste through law, policies and welfare. Thus, the foundations of the modern Indian state were closely tied to his critique of the Hindu social order itself.

The long march of Hindutva aims to threaten this very foundation of the nation envisioned by Ambedkar. He pronounced the superiority of constitutional authority to resist the tyranny of majoritarianism. The Hindu right has perverted the meaning of democracy as simply a rule of the majority, stripping democracy of its substantive meanings. It has not forsaken the democratic structure for its pursuit of a Hindu nation, instead persistently demoted the core political values of freedom of speech, and liberty as threats to national unity and sovereignty.

The peculiar political situation today has been such that the Hindu right has not only captured the political space but also regulated the social in its own vision of Hindu society. Unlike the left-liberal political organisations in India, the right-wing has a unique advantage- it has a mass organisation Rashtriya SwayamSevak Sangh (RSS) that has spread like a ‘tentacular’ organisation mobilising every social group in India (Ahmad, 2020; Jaffrelot, 2005). Another peculiarity of the Hindu right is that it aspires not only to capture political power but also to bring about a social transformation of the entire society. The ‘Sangh Parivar’ describes itself as a cultural organisation with no relation to politics. However, it is no secret that the RSS benefits from the entrenchment of power in the hands of its political outfit, the BJP. The neglect of social space by the liberal-left by narrowly focusing on gaining political power alone, has festered a vicious attack of the social on the political. There is no contention that the Congress party has failed to proactively counter the right-wing. Perhaps, except Nehru, none of its leaders truly grasped the intentions of the RSS.

The BJP which subscribes to the ideology of Hindutva has no intentions of emancipating Indians of social hierarchies and prejudices. Its philosophy and conception of an organic society envisions preserving structures of authority that Ambedkar recognised as detrimental to society. Since 2014, the populist turn has deliberately put the caste question off the table. Any discussion of caste is seen as conspiratorial of anti-Hindu or anti-national forces that can jeopardize the fundamental unity on which the fragile veneer of the nation rests. The repercussions of this pan-Hindu identity include the creation of a broad alliance of caste groups under one banner of pan-Hindu identity. It also redirects political energies away from caste reform and welfare politics towards crude identitarian politics, resulting in a singularity of identity on religious terms, taming life and politics into a farcical, reductive binary of Hindus and Muslims. The right magnifies the existing social antagonisms to create a general distrust and animosity in society. The Hindu-Muslim binary is hardened to fuel a politics of fear where the majority Hindu community is made to be the victim at the behest of the Muslim minority. However, underneath the rhetoric of ‘Hindu unity’ lies a game of caste arithmetic. The Hindu right is aware of the impediment of caste in fracturing a sense of political unity of the majority. The numerical majority of the Hindus relies on the erasure of reality of the existence of several caste minorities that constitute this ‘majority’. The Hindu right presumes an essential unity of the Hindus as an existential necessity thereby, deliberately erasing the fundamental division of the society by caste. Though the Hindu right snubs the politicisation of caste, it has not shunned the instrumental use of caste politics itself.

The question then is, if the Hindu social order is, as Ambedkar had rightly pointed out, deeply fragmented on the basis of caste, how has the Hindu right overcome these basic contradictions in society? More importantly, has the rhetoric of Hindu unity resolved caste fissures in favour of the right-wing entirely? Though these questions are beyond the scope of this paper, it is pertinent to keep in mind the limitations caste politics is capable of putting on the Hindu right-wing, without glorifying their resistance to Hindutva politics as inherent in their politics.

The contention here is that narrow attention to the exclusion of religious minorities while ignoring the process of inclusion of caste minorities occludes any serious consideration of the right’s workings in both the social and political fields. The BJP is striving to bring different sections of caste groups under its sphere of influence by pursuing a cultural strategy. Culture bridges the disparate entities of the social and the political. The Right hammers the significance of culture in the sustenance of the idea of the Indian nation. There are three valuable points to be made here with respect to the Sangh’s ambiguous relationship with caste. The Hindu right does acknowledge the impediment of caste to Hindu unity, albeit it does not see the hierarchical structure and its harmful impact. However, what explains the appeal of such an ideology among the lower castes themselves? The answer cannot be explained by Srinivas’s ‘Sanskritisation’, there is more to it. First, the Hindu right speaks an emancipatory language of dignity and not liberation. Second, the political value of equality is reinterpreted as maintaining social harmony, which essentially allows hierarchies to exist without the possibility of emancipation from it. Samajik Samrasta or social harmony is one of the key tenets of RSS’s approach towards caste groups in India. Third, it stokes sentiments of caste pride as Hindu pride which is to suggest that one can celebrate their caste difference as long as they affirm their belonging within the Hindu-fold. Thus, the Hindu Right-wing is not only dictating the terms of inclusion of caste groups but also actively carving a new political subjectivity. For this, the right-wing uses cultural myths, local icons and festivals. Birsa Munda, among others, is resignified as a ‘Hindu’ warrior and local deities become avatars of Gods and Goddesses in the Hindu pantheon. In his work ‘Fascinating Hindutva’, Badri Narayan (2009) has detailed the mobilisation strategy of the RSS in reinterpreting Dalit’s Hindu past, unifying them under the metanarrative of Hindutva. What is remarkable is how the Right continues to communalise issues while also actively pursuing and accommodating caste groups. For decades, caste politics seemed to pose an effective counter to the hegemonic project of religious nationalism. Is there a synergetic relationship between caste and Hindutva politics today? Does the use of cultural strategies by both identity movements create a conducive interface for possible interactions? It is in the context of the mobilisation of Dalits by the BJP that Ambedkar’s appropriation must be seen.

The sudden admiration for Ambedkar by the BJP is a carefully crafted strategic move that aims to consolidate the lower caste behind it. The appropriation of Ambedkar’s legacy is a symbolic power move to commandeer Ambedkar’s image without its content (Tharoor, 2025). Ambedkar’s views on communal relations between Hindus and Muslims have often been overlooked. Interestingly, the most cited book of Ambedkar by the Hindu right is ‘Pakistan or the Partition of India’ written in 1945. The book offers rich insights into the nature of communal relations in India, but the Hindu right selectively quotes from the text and misappropriates Ambedkar for peddling its own communal narrative as will be discussed in the paper. The following sections of this paper argue that Ambedkar’s affordance to the centrality of caste in social explanation can facilitate a ‘de-binarisation’ of the Hindu-Muslim discourse, while also putting welfare goals and material development back on the agenda. Through the thematic exploration of Ambedkar’s way out of the communal deadlock, this essay underscores the need for political reimagination while simultaneously resisting distortions of Ambedkar by the Hindu right. The first section of the paper discusses the appropriation of Ambedkar. The second section dabbles with the possibilities for initiating a dialogue between Savarkar and Ambedkar’s ideas of nation and caste. The penultimate section presents Ambedkar’s alternative to the communal question.

- Saffronising Ambedkar ?

Image Source: Google Images

A few days ago, Narendra Modi claimed that a developed and inclusive Bharat would be a true tribute to Ambedkar. He has been high on Ambedkar’s symbolism and has claimed more than once that no party has honoured Ambedkar more than the BJP. A huge statue of Ambedkar has been built in Maharashtra and the Government is organising a ‘Panchteerth’ which identifies five ‘holy sites’ where Ambedkar spent the different phases of his life. One can shirk this away as a cheap political tactic but when one juxtaposes this against the visible political implications, the picture seems worrying. Traditionally, Dalits have not voted for the party. But in 2014, the BJP surpassed both the Congress and the Bahujan Samajwadi Party (BSP) by attracting a larger vote share (Verma, 2016). Moreover, the vacuum in Dalit leadership in other political parties, especially the Congress and the weakening of BSP politics has provided germane conditions for BJP’s penetration into the Dalit fold. Thus, the appropriation becomes essential, as the BJP aims to mobilise the cultural and political memory of Ambedkar that Dalits across communities and regions in India continue to hold dear, thereby, giving Ambedkar a new meaning as a ‘nationalist’, hailing him as a social reformer with the likes of Arya Samajists and Brahmo Samajists.

In 2015, in a seminar organised in New Delhi, Dr. Krishna Gopal (Former Jt. General Secretary of RSS) described Ambedkar in the following words: “Besides being a champion of the untouchables, Ambedkar was, first and foremost, a nationalist, a virulent anti-Communist and had immense faith in Hinduism; he was against Brahminical structures but some of his closest friends were from upper castes, while Brahmins provided him vital help at key moments in his life; he dismissed the historical theory of the Aryan invasion of the Indian subcontinent. Apparently, he also promised “shuddhikaran” or purification for those Dalits who had converted to Islam in Hyderabad state in 1947-48” (India Foundation, 2016).

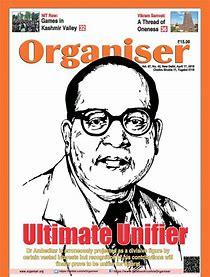

A 2016 issue of ‘Organiser’, an RSS magazine, hailed Ambedkar as the “ultimate unifier” and a “timeless leader” who provided a “glue for nation building.” The magazine claimed that Ambedkar was not against Brahmins but against the Brahmanical order and “Babasaheb felt that pseudo-Dalit movements” are merely distorting history by capitalising on “lacuna in Hindu religion, provoking Dalits to agitate” (Organiser, 2016). The article further states that Ambedkar was closer to Vivekananda than any other nationalist leaders including Tilak and Gandhi, since he equally emphasised material and spiritual progress. Further, another article in this issue said that for Ambedkar, “the nation remained a top priority” and that he had “in his heart the image of Bharat Mata…”(Organiser, 2016). Apart from misquoting Ambedkar for having said that ‘Hindu culture’ is the basis of the unity of Bharat and taking his quotes out of context, the Hindu right has embraced Ambedkar as a patriot and nationalist who wanted social reform for a “small section of the society” (Organiser, 2016). It also claims that Ambedkar converted to Buddhism and not any other religion as it is closer to Hinduism than Islam or Christianity. Thus, Ambedkar never really wanted to leave the Hindu-fold. It is true that Ambedkar converted to Buddhism after much consideration and realised that all religions practice some form of caste discrimination. Buddhism on the other hand promoted equality, fraternity and self-development to all (Ambedkar 2003, BAWS, Vol 17, part III, 2003). In the ancient history of India, Buddhism posed an effective challenge to Brahminism which had divided the society into varnas. It introduced democracy and a socialist pattern in society. Savarkar took a diametrically opposite view of history. He asserted that Buddhism weakened Hindu military prowess with its emphasis on non-violence, making it vulnerable to foreign attacks and invasions. He blamed Buddhism for the political fragmentation which ultimately weakened Hindu society. Savarkar, nevertheless included Buddhism into the Hindu pantheon as an off-shoot of Hinduism. He saw the embrace of Buddhism by the Dalits, especially Ambedkar’s eventful conversion as a threat to Hindu unity.

Image 1: Organiser’s April 2016 Special issue on Ambedkar

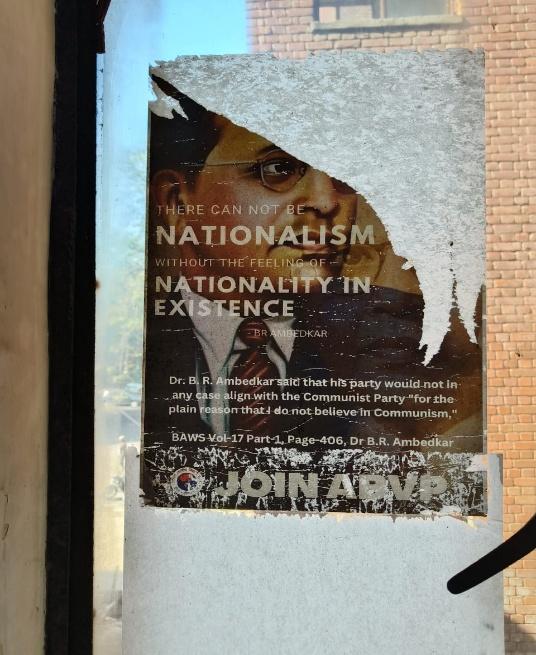

Image 2: An ABVP Poster in JNU (clicked by Sanjana)

- The Anti-heroes of the Twentieth Century India: Reading Savarkar and Ambedkar together

The two towering figures who continue to draw renewed fascination for right-wing/Hindu nationalists/BJP include Savarkar and Ambedkar. Though they both come from different social backgrounds, they both represented strong alternatives to the Indian nationalist movement led by Gandhi and Nehru. Their ideas did not have appeal with the masses initially, but were picked up later by their ‘devout’ followers. Both the ideas stood as a critique of the secular state, albeit on different ends of the political spectrum.

The RSS wove Ambedkar and Savarkar together in discourse as not friends, but as possessing ‘mutual admiration’ for each other. It is true that Ambedkar appreciated Savarkar for having clarity on communal questions, unlike the Congress who played the Muslims for ‘diplomacy’. Another interesting commonality between the two is Savarkar’s attack on caste discrimination and his half-baked anti-caste spirit. In his seminal biography of Savarkar, Chaturvedi (2024) notes that he participated in temple entry movements for Dalits and gave lectures on problems of untouchability. The district Magistrate of Ratnagiri in 1929 noted that Savarkar’s work could “create conflict and interfere with the work of Ambedkar in the region” (Chaturvedi 2024). Bakhle (2024) in her biography of Ambedkar, calls him a “heterodox brahmin” who was a devout nationalist but also anti-caste, while “constitutive contradiction was at the heart of Savarkar.” He differed from Arya Samajists and other Hindu revivalists who considered caste an essential feature of Hinduism. In advocating for a political Hindu unity tied to the idea of ethno-geographical conception of the Indian nation, Savarkar rejected Hinduism. He believed that Hinduism stood for dogmatic, ritualistic and traditional norms instead of Hindutva, which encapsulated the great history of Hindu people and nation better (Savarkar, 2021). Thus, “caste was regressive, ethnic nationalism was progressive” (Bakhle, 2024). Ambedkar also rejected Hinduism for its discriminatory nature and inherent caste system. He opted out of the Hindu fold entirely, while Savarkar wanted to retain the overall Hindu social structure, albeit sapped of its traditional hierarchical underpinnings including caste discrimination (Bakhle, 2024). Ambedkar’s project stood as a challenge to Savarkar’s program of constructing a pan-Hindu unity. Ambedkar claimed that the untouchables are not a subsection of the Hindus, that they are a separate and distinct element in the national life of India. The separation of untouchables from the Hindu pantheon was necessary for the upliftment of the untouchables (Ambedkar 2003, BAWS, Vol 17, Part III, pp. 248-83; Kumar and Jaffrelot, 2018).

This section, however, sees possible convergences only to diverge in radically different ways between the two of the most important thinkers of the 20th century. Caste and religion are the two important identities that have, since colonial times, dominated the discourse in Indian politics. Ambedkar is usually seen as a caste icon and Savarkar for his religious nationalism, but such a reductive reading of the two thinkers is futile. The conceptualisation of caste was central to both thinkers in not only how they defined collective identities, but also their entire political program that has continued to inspire two major mobilisations.

Ambedkar and Savarkar relied on history to redefine the understanding of their societies. Though the latter’s obsession with itihaas to create a common unified Hindu past bordered on fictional and often exaggerated accounts, he wasn’t concerned with the facts of history and freed himself from any such burden entirely. “Hindutva is not a word but history…Not only a spiritual or religious history…but history in full” (Savarkar, 2021). The past determined the course the future would take. Ambedkar, on the other hand, used history to bring to attention, how the Caste Hindus had institutionalised violence and systematically deprived the lower caste of basic resources. In his essay, “Castes in India: Their Mechanisms, Genesis and Development”(1917), he elucidates on the genesis of caste in the parcelling of a homogeneous cultural unity. He traces how the “artificial chopping of the population into fixed and definitive units” prevented different groups from intermixing, codifying social immobility. He further explains how through the “infection of imitation”, those on the lower level of caste hierarchy imbibed the practices of endogamy that tightened the hold of the caste system (Ambedkar, 1917). Savarkar’s obsession with history undermined the socio-political realities of Indian society that Ambedkar drew attention to, in the entirety of his catalogue. However, if caste were to stand as an impediment to a cohesive Hindu identity, Savarkar’s reinterpretation of caste assimilated the depressed classes by sacralising not the religious ‘Hindu’ identity per se as Gandhi did, but a cultural-territorial conception of a nation against the profanity of caste. The brotherhood among caste minorities was based not on common blood but on a shared history of exploitation of foreign rule, of recovering a lost glorious epoch within the geographical frontiers of ‘Bharat mata’ before the menace of caste broke the Hindu society into parcels. Thus, the loyalty of the ‘Hindus’ was not to their religion or traditions, but to the nation alone.

Savarkar demonstrated that the anuloma and pratiloma marriages had mixed the blood of different castes. He writes: “Some of us are Brahmans and some Namashudras or Panchamas…but Gauds or Saraswats, we are all Hindus and own a common blood” (Savarkar, 2021, p 91). He further adds that a “Hindu marrying a Hindu may lose his caste but not his Hindutva” (Savarkar, 2021, p 92). Savarkar understood how caste in principle kept Hindus from becoming a cohesive community as the other abrahamic religions and therefore, willed to proselytise Hinduism. This could not be done unless caste was dislodged but not dismantled as the authoritative principle guiding social and political union. He encouraged mixed marriages, though only between regions and not caste groups. He did not see the marriages between a Sudra and Brahmin as annihilating caste rather, devoted his energies to crafting a bond of unity between Hindus (Bakhle, 2024). Savarkar’s Hindu unity, unlike the European kind, did not focus on racial unity by blood; instead, it was the common cultural unity that formed the basis of a common Hindu identity (Bhatt, 2001). This allowed him to transcend the fixed divisions of caste. The feeling of oneness and of brotherhood could not be found in the Hindu religion which enabled caste divisions. Thus, since Hinduism had a lot of baggage, especially of caste, Savarkar differentiated Hinduism from Hindutva to make a case for a Hindu unity absolved of these fundamental problems. He held the view that the achievement of Hindu unity without eliminating caste hierarchies was futile. His precepts of Hindutva nevertheless retained the Brahmanical outlook but were modernist in spirit. His ambivalence towards caste proceeded from his fear of ‘the other’, especially the religious minorities who despite their marginal numbers, posed a grave threat to this presumed unity.

Ambedkar (1945) was clear that mixing religion with politics would prove disastrous for the survival of caste minorities if India were to be a democratic nation. He probes the sufficiency of these categories offered by Savarkar to deem India as a nation. First, Ambedkar takes up the social features of India that Savarkar mentions: race, language and culture. He argues that a Punjabi Brahmin will have more commonalities with a Punjabi Muslim than with a Maharashtrian Brahmin. He further notes that the commonalities between Hindus and Muslims are the result of certain ‘“purely mechanical causes”, and “they are partly due to incomplete conversions.” It is this ‘common environment’ that produces similar reactions and shared practices. By relying on certain common features like race, language and country, “the Hindu is mistaking what is accidental and superficial for what is essential and fundamental” (Ambedkar, 1945). Using Renan, one of the most important scholars on nation and nationalism, Ambedkar argues against the Savarkarite position that these three essentials are not sufficient to constitute a nation. What does then constitute a nation?

Ambedkar, like Savrakar and Nehru, tethered the idea of the unity of the nation to a territory but elevated its spiritual significance. The nation for Ambedkar was “a living soul, a spiritual principle” which includes the principle of common possession of the past, the rich heritage of memories and in the present, an active consent to live together (Ambedkar, 1945). Ambedkar used this definition of nation to ask Hindus and Muslims if they had something shared and common and wished to live together (Ambedkar, 1945). He adds however, that to have “suffered together” consolidates towards a “greater bond of union than joy.” If one takes into account the common historical antecedents between Hindus and Muslims to form a nation, the Hindu argument “falls to the ground” (Ambedkar, 1945). On the matter of Partition, he reaffirms his position that for a nation, a cultural territory is important, and if for the Muslims it is Pakistan then they have the right to form a nation. He then systematically reveals the contradictions in the Savarkarite position, which was also the Hindu organisation’s resolve on the partition of India. Ambedkar takes up three points of contention tabled by the Hindu Mahasabha, the President of which was Savarkar. He understands why the Hindus oppose partition as the partition of India would burst the idea that India has been a nation eternally. This would also harm the argument for a nation or an ‘akhand bharat’ idea that the right-wing professes. But then, Ambedkar asks if Hindus do not want Muslims to secede from India, why does Savarkar assert that Hindus and Muslims have nothing in common? Unity cannot be based on anything but the feeling of oneness. However, as history has told us, Hindus and Muslims do not have anything in common and no desire for unity, echoes Ambedkar. The second point of contention is that the weakness of the defence of India is a concern. How does having Muslims, who are presumably an internal enemy of India guarantee the security of the nation? The third point of difference asks Hindus whether, by not allowing the creation of Pakistan, the communal problem would be solved. Even with the creation of Pakistan, the communal problem in Hindustan would not be resolved.

Ambedkar makes his intentions on the state of Muslims in a post-partition India very clear: “While Pakistan can be made a homogenous state by redrawing its boundaries, Hindustan must remain a composite state” (Ambedkar, 1945 p. 104). He asks Savarkar straight-forwardly his intentions with non-Hindu minorities in his Hindu Raj. If swaraj for him bears the stamp of a Hindu Raj, by this logic, Muslims are a nation too. Savarkar and Jinnah are much closer in principle than apart. However, unlike Jinnah who believes that the non-Muslim minorities in the newly created Pakistan will live under the same constitution as the majority, Savarkar maintains a sinister silence. He maintains that Savarkar is “stripping Muslims of all the political privileges has secured so far”, thereby creating the most dangerous situation for the security of India. He writes, “Why Mr Savarkar, after sowing the seeds of enmity between the Hindu and the Muslim nations should want that they live together under one constitution and country is difficult to explain” (Ambedkar, 1945, p. 133).

Ambedkar was aware of Savarkar’s intentions and the repercussions of a Hindu supremacist ideology of nation. He made it plenty clear that Hindu nationalism had no place in India. The impossibility of aligning a deeply divided society into one homogenous Hindu whole troubled Ambedkar less than it does today to anybody living through these times. To revisit Ambedkar today is significant for two reasons: he did not see Hindus and Muslims as separate, instead believed they had much in common; the agenda of the untouchables was prioritised less over the idea of secularism, that the Muslim minority were the only ones in need of protection; and lastly, to question the idea of Hindu ‘majority’ itself.

- Ambedkar’s Alternative to the Communal Question

Despite India’s commitment to secularism since its political inception after a traumatic partition, communal contentions have failed to wane, and in the present, have acquired a vitriolic turn than ever before. At the time of severe communal clashes during the partition, thinkers addressed this situation. Nehru believed that economic issues would take precedence over communal issues as India focused its energies on development. Ambedkar, on the other hand, recognised early on that the communal question could not be remedied by economic solution alone; instead, it required cultural and even spiritual solutions. Like many of his contemporaries, Ambedkar entertained the idea of cultural unity of the Indian nation, albeit with caution. Like Nehru, he believed that Hindus and Muslims could live together as a nation, provided the minorities were guaranteed constitutional safeguards. The constitution is a living proof that the idea of India for Ambedkar was that of ethnic heterogeneity strung together with an overarching cultural homogeneity. In his essay, Castes in India (1917), Ambedkar belabours an important point: the homogenous cultural unity of India. He says: “Ethnically all people are heterogeneous. It is the unity of culture that is the basis of homogeneity” (Ambekar, 1917) He argued further that the parcellisation of this culture was ensured by the principle of endogamy, as the caste system entrenched itself across India.

The Savarkarite proposition suggested otherwise. It used cultural homogeneity to make a case for a pre-existing united Hindu nation, but excluded certain religious minorities. The Hindu Right, however, has selectively used Ambedkar’s above-mentioned quote to argue that Ambedkar also considers cultural unity as the basis for a Hindu nation and the existence of caste as a ‘unifying factor’ (Panchjanya, 2024), thereby justifying the existence of caste system as essential for maintaining cultural unity of the nation. Ambedkar acknowledged that caste was a common feature across India, but it was also the bane of the society that divided it. He also alluded that caste was the organising principle for all of Indian society and that religious divisions were “superficial” and not as fundamental as caste. However, the colonial imprints of reducing Indian history to religious conflicts and a history of Hindu-Muslim strife blurs social experiences and disjoints academic analysis from social facts. The reductive nature of Indian politics into categories of religion alone creates more problems, as Hindu nationalism and Muslim nationalism have “co-produced each other”, ignoring that a Dalit Bahujan and a Muslim Bahujan have more common issues of bread and butter that require redressal but get side-tracked in the secular-communal discourse (Ansari, 2017).

The invisibilisation of caste in the Hindu-Muslim discourse today, by even those opposing the right-wing, plays into the metanarrative of Hindu unity that comes at the cost of both Muslims and Dalit-Bahujans. Here, Ambedkar’s description of the relationship between Hindus, Muslims and the Untouchables is pivotal. Unlike Savarkar who saw nothing in common between Hindus and Muslims, Ambedkar believed that caste Hindus and Muslims share a “history of political power and rule, united by a symbolic power rather than systematic violence” (Kapila, 2021, pp. 160-162). He maintained that Hindus and Muslims were neither fundamentally different nor that they were foes. He describes their relationship as one of “estrangement” which highlights the fractured nature of coexistence in society. He further argues that Hindus and Muslims were never truly integrated to begin with, but lived in a state of mutual exclusivity without much interference in each other’s practices and customs. The relationship between Hindus and Muslims was not antagonistic. Ambedkar said that the chasm between Hindus and Muslims was religious and not social, but between Hindus and untouchables, it is both. Unlike the master-slave relationship between the untouchables and caste Hindus, the contentious relations between the Hindus and Muslims is merely of estrangement. “Social unity” in terms of race and language between the Hindus and Muslims was “honeycombed” (Kapila, 2021, p.p. 328-332), suggesting the complex and intertwined nature of his nuanced understanding of communal relations. This estrangement and not separation is actually useful. It is more realistic in its assessment than an over-whitewashing of eternal harmony and love. Ambedkar believes that Hindus and Muslims had by the time of partition, reached a point of intractable animosity. They did not have any consciousness or desire for unity. He disagrees with the Gandhian and popular nationalist position that the differences between Hindus and Muslims were a colonial construct alone. He instead argues that the divide-and-rule policy would not succeed in the first place if there were not pre-existing issues of co-existence. The Hindu-Muslim differences had a spiritual character, of which political antipathy was only a reflection forming a “river of discontent” (Ambedkar, 1945). Moreover, the inherent antagonism kept Hindus and Muslims apart on matters of faith, but also made social assimilation a challenge. The possibility for cordial brotherhood exists and needs to be worked out. While a social union existed, the possibility of a political union was challenged.

He raised two caveats with regard to the possibility of Ha indu-Muslim union: the role of government in unifying the Hindus and Muslims and the question of social-political reform. Ambedkar considered the possibility of the government acting as the unifying force. However, the Indian society which was deeply divided on race, and language prevented any fusion among the people. The government alone cannot make them into one nation. He further argued that political unity alone would not be sufficient for ensuring a peaceful co-existence. The shortcomings of the Indian secular state can be traced in the neglect of achieving a moral and social unity between the two communities that Ambedkar deemed necessary. He said, “Without social union, political unity is difficult to achieve” (Ambedkar, 1945). A mere lip service to political unity obscures and glosses over the social realities of discords and divisions that exist in society between the communities. Further, Kapila (2021, 2019) underscores Ambedkar’s agonism that saw conflicts as necessary for challenging oppressive structures and their transformative power in creating a just and equitable society. Engaging with these conflicts is productive in converting them into agonistic politics, which made way for peaceful resolution and aided in the creation of a new fraternity (‘Ambedkar’s agonism’ cited in Kapila, 2019). Thus, Ambedkar was aware of the importance and productiveness of conflicts. The problems of the social needed political solutions, and real disagreements and conflicts needed to take an agonistic form otherwise, the goal of achieving consensus would depoliticise them which can later emerge as extremism or backlash (Mouffe, 2005).

Further, Ambedkar also addressed that social issues required reforms. He said, “the Muslim society in India is afflicted by the same social evils as the Hindu society” (Ambedkar, 1945). He berated the Muslims for having no place for secular categories in their politics and being subservient to the principle of religion. The lack of organised social reform in the Muslim community is “disturbing.” Ambedkar’s steady critique of both Hindus and Muslims steers clear from any accusations of appeasement to either community and takes a firm stand against the evils of both the communities. “I have no hesitation in saying that if the Mahomedan has been cruel, the Hindu has been mean; and meanness is worse than cruelty.” (Ambedkar, 1936). He however, empathises with the Muslim community, that being in a predominantly Hindu environment, the fear of ‘de-musalmananizing’ makes the preservation of religion steadfastly as a way of preserving their identity itself (Ambedkar, 1945). However, this has resulted in social stagnation which translates into their political life as well. The secular politics in India has also always posed the question of minority as ‘religious’ questions while ignoring the material issues of the minority. Thus, the question of a Muslim even today, is always a matter of religion. This furthers a binarised narrative of Hindu-Muslim unity that is “bound to generate a conspiracy of silence over social evils.” The current dispensation and the counter to it have perverted the discourse of Hindu-Muslim unity to religious categories. Internal antagonism in Hinduism is posed in direct relation to understanding Hindu-Muslim discord. Ambedkar steps out of the binarised discourse of Hindu and Muslim, unlike his peers. His understanding of caste not only redefines the relationship between Hindus and Muslims but also carves a special space for political possibilities for caste minorities. It is also useful to question the majority-minority binary that has troubled liberal thought and unintentionally strengthened the right-wing narrative of the majoritarian claim. Caste still remains the fundamental organising principle of the country and as Ambedkar had noted, the communal problem was more superficial in nature.

- De-binarising Minority-majority

Ambedkar in his speech ‘Communal Deadlock and a Way to Solve it’, addressed in May 1945 argued for an alternative approach to the communal question. He believed that the communal deadlock was solvable and had remained a thorn in the political life of the nation because the leaders had approached it incorrectly. “The defect is that it proceeds by methods instead of principles” (Ambedkar 2003, BAWS, Vol 1, 1979). The majority’s insistence that the rule of majority is sacrosanct and must be maintained at all costs is the root cause of communal issues. Savarkar, Nehru and Gandhi were concerned more with maintaining the numerical majority of Hindus that would benefit only a section of the population while jeopardising the development of minorities, especially the untouchables. Ambedkar argued that the majority rule was not divine, natural or accepted in principle but was “tolerated as a rule.” The political majority absorbs the point of view of the minorities and so, the minority does not care to rebel against the decision. Thus, he suggests the abandonment of the principle of majority rule for Hindus itself (Ambedkar 2003, BAWS, Vol 1, 1979). He asks the Hindu community to make sacrifices and that the minorities’s rights must be constitutionally safeguarded. Further, Ambedkar distinguished between communal and political majority. While the latter was born into and not made, the former needed to be constantly made into a majority. He recognised that the categories of minority and majority were not rigid and watertight compartments, instead a majority is always made and unmade. The recognition of minorities by the colonial administrative practices had resulted in the creation of a “statutory majority”, but to convert it into a political unity would be impossible given the fragmentary nature of Hindu society (Kapila, 2021).

This adherence to the principle of majority rule made impossible the conditions for separate electorates for the Scheduled Castes. Making the untouchables a distinct entity from the Hindu fold would threaten the unity of the Hindu, thus implicitly so, the nation itself. To maintain the numerical majority of the Hindus was essential for the nation. Ambedkar asks if Sikhs and Muslims could have a separate nation, why couldn’t the caste minority. Moreover, it also allowed the Hindus to turn a blind eye to social discrimination. Thus, Indian nationalism, says Ambedkar, had developed a new doctrine of “divine rule of the majority” to rule the minorities according to the wishes of the majority. “Any claim of the sharing of power by the minority is called communism. While the monopolising of the whole power by a minority is called nationalism” (Kapila, 2021). The numerical communal majority is not equal to the political majority.

Extrapolating this argument, Ambedkar’s insistence that a political majority is made and unmade forces us to rethink the categories of a ‘Hindu’ majority. This coaxes us to focus on the process of making a political majority by accommodating different caste minorities. The liberal-secular camps need to focus on not religious minorities alone but caste minorities as well. Ambedkar’s alternative to communal deadlock puts caste consideration back into political life, finds newer ways of forming alliances between religious communities on common agendas, and compels us to rethink the category of majority and minority.

This section discussed the ideas of nation and the communal question of Ambedkar by reading him together with Savarkar. Kapila (2021) notes that both Savarkar and Ambedkar were redefining political subjectivity- their locus of sovereignty was not in the state but in the political subject. For Ambedkar, popular sovereignty should not be equated with the majority. Laying the foundation for Indian republicanism, Ambedkar brought together territory, culture, and commonality—elements that Savarkar also used as the basis for his idea of popular sovereignty—but in ways that were more accommodating of plural groups and identities. Ambedkar placed the solution for communal problems not in the political but the social. This gives a long-term agenda and a program for the left-progressive camps to capture the realm that it has increasingly abandoned- the social. Identity politics today has pressed the issue of identity in cultural terms alone, alienating material questions. Ambedkar’s insistence on the intricate relationship between social and political alludes to the Frasarian (1998) insistence on merging claims of recognition with material redistribution. Thus, seeing current issues through Ambedkar’s lens coaxes a more nuanced answer to: How do we reimagine modes of democratic living today?

Conclusion

The Hindu right’s rise to power presents new challenges to the secularism and democracy of the nation and has exposed its limitations as well. Both failed to address caste inequalities as well as deprivation among Muslim groups. Perry Anderson (2012) in his book The Indian Ideology, doubts the intentions of the secular promise of the Indian state by asking what it did to alleviate the economic well-being and conditions of the Muslims. Anderson remarks that “Indian secularism is Hindu Confessionalism by another name.” The narrow approach of secularism to the question of minorities has left caste issues marginalised. Additionally, the identity politics of caste remains stale for its lack of long-term vision. Together, they have contributed to the growth of the Hindu right-wing among other factors. As one looks to the past, to Ambedkar for answers, his alternative approach to solving the communal question stood in contrast to Jinnah, Gandhi, Nehru and even Savarkar’s proposition. He chastised all of them equally. Ambedkar did not merely turn a blind eye to the problem of communalism and especially, the demands for Hindu Raj. He took the challenge head-on and addressed it without undermining the issue of caste that for him, remained an utmost priority throughout. He did not buy into the overly rosy picture of Hindu-Muslim unity as Gandhi did nor did he stop short of calling Savarkar illogical and irresponsible for putting India’s security in danger. Further, Ambedkar categorically rejected the Hindu Raj in the same breath as he denounced the Muslim league. He made a principled rejection of Hinduism’s caste system calling it a monster and did not shy away from calling out Muslims for their inability to think beyond their religion. The secular politics finds itself in a tricky position as the Right takes up the issue of reforming Muslim women (for instance, Triple Talaq and UCC) as a cover for the criminalisation of Muslim men. Giving up on reform altogether in the name of ‘protecting minorities’, on the contrary, only aggravates the problem of caste discrimination and gender oppression present across religious minorities as well. Ambedkar’s solutions provide a way out of this fix.

Ambedkar’s views on nation focus on an inclusive nationalism which unlike Nehruvian nationalism, does not erase and invisibilise caste. Ambedkarite nationalism can bust the Hindu unity myth as well as give a social-economic programme to envision a liberating future. Ambedkar understood that mere identification of citizens is not enough to cultivate a bond of fraternity among citizens, he proposed a psychological unity as the basis for nationalism (Mohan Lal, 2024). He believed that dismantling caste was necessary for strengthening India’s unity. The caste system intensifies the fragmentation which poses a challenge to a collective imagination of cohesive national identity. Thus, fostering an inclusive sense of unity that transcends caste division as vital for establishing a genuine nationhood. In the making of a modern nation based on the principles of liberty, equality and justice, Ambedkar set a profound vision for the nation that had to overcome the contradictions of Indian democracy and its resolutions, to fight its own inner demons while encouraging constant self-introspection. Any political imagination today must ensure welfare and equality in the social realm, else political liberty and power make very little sense, resulting in further degeneration of democracy. Bringing in caste not supplemented by a cultural logic of recognition alone, but to pose questions on the larger structural and material inequalities can challenge the superficial symbolic inclusion of caste minorities into the Hindu fold. Ambedkar’s emphasis on both material welfare and cultural recognition reminds the progressive identity politics to tackle the onslaught of the right-wing virulent version. Democracy today needs a new language of inclusion and a mindful negotiation of solidarities while keeping intersectionalities of power and structures in mind. A solidarity that professes both a genuine acknowledgement of caste hierarchies and the resultant distrust of dominant savarnas as well as recognises the interconnectedness of struggles against Hindu right-wing and moves towards a common goal.

Democracy has to mean more than simply defeating the Hindu right-wing today. “The roots of democracy are to be searched in social relationships, in the terms of associated life between the people who form a society” (Ambedkar 2003, BAWS, 1979). Caste politics as well as the mainstream left-liberal politics needs to go beyond language of reservation and act swiftly as the right-wing marches onwards, offensively. Thus, a call for reclaiming Ambedkar’s revolutionary spirit beyond mere symbolism is urgent and necessary (Teltumbde, 2024). This paper attempted to critically engage with Ambedkar’s ideas and legacy to make a case for a transformative political imagination in times of social paranoia and hopelessness. Though Ambedkar’s legacy is churning between the colours of blue and saffron- it is not him who needs saving but us, and Ambedkar alone can rescue Indian democracy from its current contradictions.

References:

Ahmad, Aijaz. India : Liberal Democracy and the Extreme Right. Hyderabad: Navatelangana Publishing House, August, 2020.

Ambedkar, B R. Annihilation of Caste. 1936. Reprint, New Delhi: Rupa, 2019.

Ambedkar, B R. Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development . Vol. XLVI. Indian Antiquary, 1917.

Ambedkar, B R. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches. Maharashtra Education Department, 1979.

Ambedkar, B. R. 2003. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 17, Part III. Edited by Vasant Moon. Mumbai: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra.

Anderson, P. The Indian Ideology. London ; New York: Verso Books, 2021.

Badri Narayan. Fascinating Hindutva Saffron Politics and Dalit Mobilisation. Los Angeles Sage, 2009.

Bakhle J. Savarkar and the Making of Hindutva. Princeton University Press, 2024.

Bhatt C. Hindu Nationalism: Origins, Ideologies and Modern Myths. S.L.: Bloomsbury India, 2020.

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar. Pakistan or Partition of India. Thacker & Company, 1945.

Jaffrelot C. The Sangh Parivar. Oxford University Press, USA, 2005.

Kapila, S. Violent Fraternity. Princeton University Press, 2021.

Kumar N., and Jaffrelot C. Dr. Ambedkar and Democracy : An Anthology. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Lal, Krishna Mohan. “Dr. Ambedkar, the Architect of Inclusive Indian Nationalism.” Outlook India, December 6, 2024. https://www.outlookindia.com/national/dr-ambedkar-the-architect-of-inclusive-indian-nationalism.

Mouffe, Chantal. On the Political. London: Routledge, 2005.

Savarkar, Vinayak Damodar. Essentials of Hindutva. New Delhi, India: Global Vision Publishing House, 2021.

Singh Kumar M. “Honouring the Legacy of B R Ambedkar: Know the Panchteerth of Architect of Indian Constitution.” Organiser, August 18, 2023. https://organiser.org/2023/08/18/190594/bharat/honouring-the-legacy-of-b-r-ambedkar-know-the-panchteerth-of-architect-of-indian-constitution/.

Singh S.P. “Cover Story : Rekindling Reformist Legacy.” Organiser, April 11, 2016. https://organiser.org/2016/04/11/117634/bharat/cover-story-rekindling-reformist-legacy/.

Singh, Swadesh. “Revisiting Ambedkar’s Idea of Nationalism.” India Foundation, July 15, 2016. https://indiafoundation.in/articles-and-commentaries/revisiting-ambedkars-idea-of-nationalism/.

Teltumbde A. Hindutva and Dalits : Perspectives for Understanding Communal Praxis. Los Angeles: Sage, 2021.

Teltumbde A. Iconoclast: A Reflective Biography of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar. Viking, 2024.

Tharoor S. “Competitive Adulation of B R Ambedkar.” The New Indian Express, January 9, 2025. https://www.newindianexpress.com/opinions/2025/Jan/09/competitive-adulation-of-b-r-ambedkar.

Tilak V. “Cover Story : Timeless Leader.” Organiser, April 10, 2016. https://organiser.org/2016/04/11/67233/general/r54739cef/.

Verma, R. “Desperately Seeking Ambedkar.” The Indian Express, April 29, 2016. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/desperately-seeking-bhimrao-ambedkar-dalit-voters-narendra-modi-bjp-congress-2776888/.

Sanjana (She/Her) is pursuing her PhD from the Centre for Political Studies, JNU. Her research focuses on Right-wing politics in Karnataka and its interaction with Caste, linguistic and regional identities. Her research interests include Indian Politics, Right-wing mobilization in India, Cultural Studies, Women Studies, Cinema and Representation.

Leave a comment