Theme- SATIRE, HUMOUR AND POWER

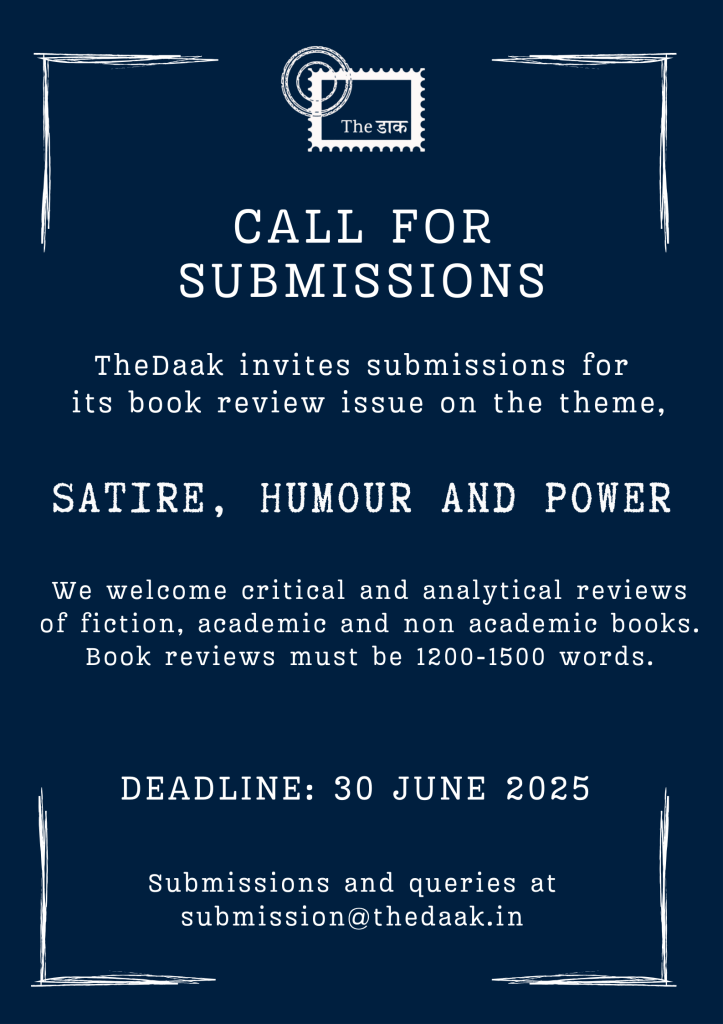

TheDaak invites book review submissions on the theme Satire, Humour and Power for its July 2025 issue

SATIRE, HUMOUR AND POWER

Humour is as ancient as human civilization. The traditions of folklore and Panchatantra were cloaked by incisive satirical critiques, irony and narrative charm. In a similar vein, the courtly tales of the Mahabharata served as a poignant satirical commentary on political ambition, human fallibility, and the fragility of moral ideals. The Bhakti-Sufi traditions and dohas (verses) of Kabir challenged religious orthodoxy and ridiculed dogmatic practices, calling out the contradictions between outward ritualistic worship and inner morality through irony and paradox.

From the jests of Socrates to the grotesque characters of Aristophanes, from Shakespeare’s fools to the cartoons of modern-day political satirists, laughter has followed power like a shadow. Philosophers like Plato viewed laughter with suspicion—associating it with disorder and moral looseness, while Aristotle saw it as a uniquely human trait, hinting at a more positive function.

Satire and humour illuminate the fragile dance between truth and illusion, authority and freedom, despair and hope. They do not provide definitive answers, but they provoke necessary questions. They remind us that wisdom is not always solemn, that critique need not be humourless, and that the deepest truths may wear the mask of comedy.

It cannot be placed in a pigeonhole, it has an inherent duality wherein the art form competes with the critique. As a literary form, satire chooses a subject matter to ridicule through the wit of the author, one that could range from observations of the banal, mundane, everyday; risque political questions; speaking truth to power to ethically envisioning humanity through the creation of the absurd, acting thus as a pedagogical tool.

Satire, unlike general humour, is intentional in its aim. It seeks to expose folly, vice, and hypocrisy through ridicule. The satirist, whether Juvenal in ancient Rome or Jonathan Swift in Enlightenment England, or Narad muni in the Indian religious tales, dons the mask of the jester to speak difficult truths. In this way, satire becomes a form of moral philosophy, less concerned with abstract principles and more with lived contradictions.

Yet satire walks a tightrope. It must be intelligent enough to illuminate hypocrisy, yet accessible enough to reach the public. It thrives on ambiguity, so much so that it can be misinterpreted as cynicism or cruelty. Here, the ethics of satire come into play: when does satire punch up and when does it punch down? This question reveals its philosophical core that satire can not be neutral. It is a weapon, and like all weapons, it demands responsibility in its use.

Humour more broadly can be a psychological and existential relief. Sigmund Freud argued that jokes allow the unconscious to express itself safely. Henri Bergson saw laughter as a social corrective, punishing rigidity and promoting adaptability. But Viktor Frankl, writing from the horrors of Auschwitz, suggested something more profound, that humour can be an existential act of resistance, a refusal to be reduced to suffering alone.

In totalitarian regimes, jokes become underground currencies of truth. In societies gripped by fear or repression, the absurd becomes a form of dissent. Laughter, then, is not escapism, it is emancipation. It signals the survival of a critical mind. Philosophically, this positions humour as an antidote to nihilism. Where reason is silenced, the joke survives.

Far from being a mere personal, individualist response, humour can function as a potent form of emotional capital that fosters collective feeling, solidarity and catharsis. Satire, as a genre, becomes a means for voicing dissent in tempestuous epochs. It begins to compensate for the sense of powerlessness that oppressed feel in humanity.

How does seemingly innocuous humour destabilise hierarchies of power and imagine alternative social realities? What are the ethical and political stakes of laughter for marginalised communities? What affective responses does humour produce, how?

Despite its emancipatory capacity, humour can also, most definitely exclude, alienate, or desensitize. Irony can become a shield to avoid commitment or responsibility. In our digital age, irony is often flattened into memes, and satire diluted by the very systems it seeks to critique. The satirist risks becoming part of the spectacle. Moreover, the audience’s interpretation determines the success of satire. A work intended as critique can be co-opted by those it condemns. The ambiguity that empowers satire can also neuter it. In this way, satire mirrors philosophy itself forever caught between clarity and complexity.

Discussions on books that speak to the theme of Satire, Humour and Power including, but not limited to:

- Satire and Resistance

- The Ethics of Ridicule

- Humour and Social Hierarchies

- Humour and the Public Sphere

- Censorship and the Limits of humour and Satire

- Colonial Legacy of Satire and Humour

- Religious Satire and Blasphemy

- Satirical Performance and the Body

- Digital Satire and the Meme as Political Weapon

Please send your book reviews to submission@thedaak.in

The deadline for the same is 30th June 2025. This issue is due for publication on 15th July 2025. Book reviews should ideally be 1200-1500 words.

Please note that if you are looking for a book recommendation on the current theme or want to discuss your book with our editorial team, you can write to us at editor@thedaak.in

Leave a comment