by Alisha Afrin

Museums have traditionally been known as static and quiet spaces that exhibit pieces of art and historical events. Today, however, they are rapidly transforming into dynamic, vibrant, and interactive spaces. Museums in India have been embracing immersive technologies. This article analyses two such technologies, namely Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality and their applications. Drawing upon the insights from Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital, Jean Baudrillard’s notion of simulacra, and Fredric Jameson’s critique of commodification, the article delves into the modes via which these technologies are reshaping the representation and consumption of art and history in museums today.

The New Museum Experience

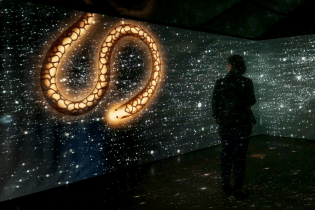

Augmented Reality overlays digital information onto the real world, transforming the way the information’s consumption is mediated, as the overlaid content is now made accessible through smart glasses, mobile devices, tablets etcetera. On the third floor of the National Museum in New Delhi, with the application of AR, as one stands in front of the concave screens displaying Ajanta cave, one can see the faded outlines slowly come alive in three dimensional details, sometimes even with colours . On the other hand, Virtual Reality transports the visitor into a fully simulated environment, be it a 270-degree view of scriptural depiction or a 360-degree view of a historic site. A famous example of VR being the 360-degree exhibition of the works of Van Gogh that took on the world with its groundbreaking immersive experience inside the painter’s dreamscapes. Both these technologies offer new ways of experiencing culture which are interactive, multi-sensory, and deeply engaging, while also raising questions about authenticity, accessibility, and what exactly it means to “experience heritage” in a digital age. The French thinker Pierre Bourdieu’s framework becomes relevant here. He outlines four types of capital: cultural capital consisting of art and history; economic capital which allows the buying of tickets; social capital which entails one’s connections and networks, and symbolic capital which shapes one’s social prestige and position. These types, Bourdieu notes, aren’t mutually exclusive, and impact, and are impacted, by each other.

Delhi has seen a surge in such experiences with the coming of new age museums, workshops, and exhibitions. In May 2024, the Van Gogh 360-degree Exhibition brought the painter’s images into life via immersive storytelling of his iconic works like Starry Night, Sunflower etc. The responses however were not without critique: some found it fascinating, while others dismissed it as a third world version compared to the glossier international editions, thus pointing towards a rather spatial difference.

The Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) has keenly embraced projection based installations that go beyond devices. As part of its exhibition named “Walking Through A Songline”, an entire room was transformed into a multi-sensory journey of an Indigenous Australian tradition recreated by means of light and sound.

The Paradox

Amidst all these, an interesting trend is revealed— audiences being more excited about the novelty of the experience rather than the deeper meaning behind it. For many, it’s about the thrill of immersion or about capturing Instagram-worthy moments, instead of thorough cultural understanding. Sometimes, technology, instead of enhancing the experience, may end up creating and selling only simulacra which are mererepresentations that, as Baudrillard explains, replace or obscure the real object . Such exhibitions often end up in a room full of people trying to capture with their phones the perfect moment for social media, instead of actually engaging with art itself. Moreover, while younger and tech savvy audiences can navigate these spaces with ease, others rely on guides to interpret technologies.

This reflects a broader tension we ought to take into account— immersive technologies aim to democratise culture by making museums exciting and relatable, but also introduce new forms of barriers and hierarchies. On one hand, these technologies claim to make the museum’s experience more interactive, but on the other hand, the infrastructures that enable inclusion generate new forms of exclusion. Accessibility depends on factors such as ticket affordability, obtaining suitable devices, and ability to use digital interfaces.

Incorporation of AR and VR projects, multiscreen displays, motion sensors etc often increase operational and maintenance costs which tend to raise ticket prices, making certain experiences financially restrictive. For instance, the prices of tickets for the VanGogh 360 experience started from ₹600 and went up to ₹1400 per person. The hierarchies become visible between those who can afford tickets and those who cannot; those who own the means such as smartphones or AR compatible devices and those who do not; those who have the digital literacy (familiarity and understanding required to effectively use AR or VR interfaces) to use them and those who do not. This tension mirrors Bourdieu’s idea of forms of capital intersecting with each other.

Reflection

The appeal of AR and VR largely lies in their ability to create hyper-real experiences. They blur the line between reality and simulation. But therein lies the risk that digital layers might overshadow the original artefacts, reducing heritage into a consumable spectacle. Cultural theories have warned about museums’ risk of museums slipping into the larger culture of commodification, where simulacra, or the replica, becomes the main attraction and not the art. As already mentioned, Baudrillard conceptualised simulacra as representations that do not refer back to the original. In the context of this article, technological display can become the primary object of fascination, while focus recedes from the original art or history. Moreover, the commodification of culture (Jameson, 1991) is evident in exhibits like Van Gogh 360. Culture itself is commodified and packaged as experience,depicting the late capitalistic nature of contemporary society.

Balancing Innovation and Authenticity

Immersive technology at its best can foster emotional connections with art and history, thereby sparking curiosity. At its worst, these technologies can risk flattening the complexity of culture into a mere spectacle. Museums, in Delhi and everywhere, must innovate to stay relevant and appealing to the citizens. Therefore, the duty of maintaining a delicate balance is important. In doing so, duties also extend to preserving authenticity, accessibility, and cultural sensitivity. Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality should serve as bridges between tradition and modernity, not as substitutes of original artefacts and history altogether. Technology is not to be resisted, but it is vital to ensure that it deepens our encounter with art and heritage instead of diluting it.

References

Jameson, F. (1991). Postmodernism, Or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press.

Leave a comment