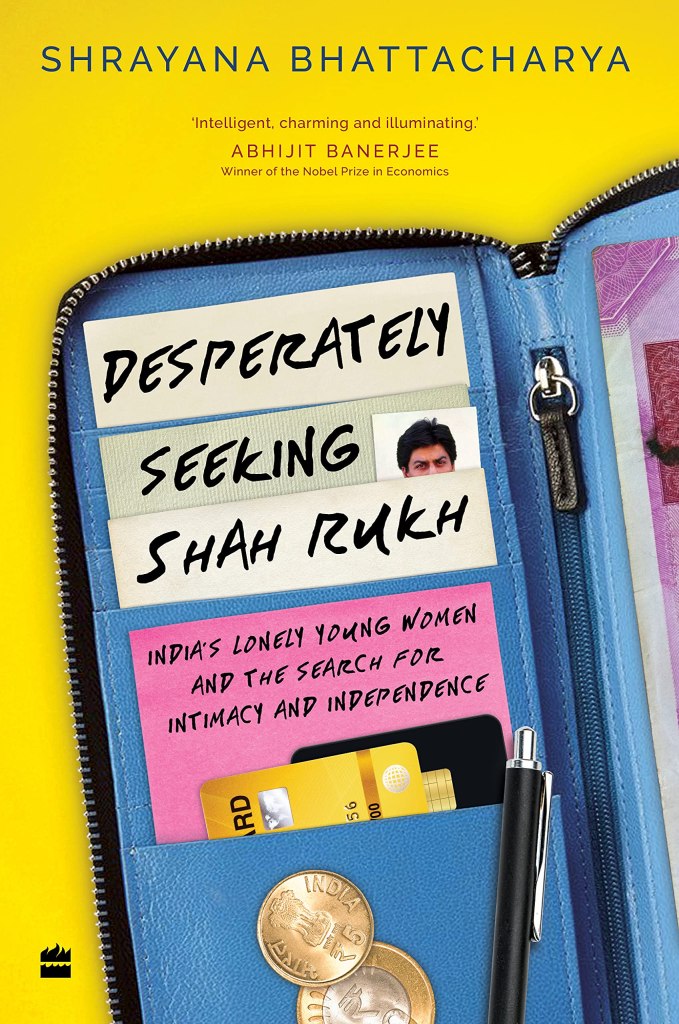

Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh: India’s Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence by Sharayana Bhattacharya, Harper Collins India, Paperback, Published: 2022, 445 + xxviii pages, ISBN: 978-93-5629-214-7, Rs. 499.00

Shah Rukh Khan, in his interview with David Letterman, informs the enchanted audiences that he is in the service of the myth of Shah Rukh Khan. Here, Sharayana Bhattacharya in an attempt to demystify the cultural phenomena called Shah Rukh through various narratives of love, life, romance, and intimacy from across the nation, gives us another account of re-mystified Shah Rukh Khan. The book will be engaging for two kinds of audiences, either academics who are interested in the economic sociology of contemporary Indian society or ardent fans of Shah Rukh’s personality and his body of work, no matter how little he is mentioned in the book. It is not a secret that Hindi cinema invests huge energy in the portrayal of male actors as larger-than-life characters, which is probably why they have been mostly called ‘heroes’ rather than ‘actors’. Through this book, the author attempts to establish the transcendental iconoclasm of a mainstream Hindi film actor who is not always macho and brave but sometimes a cruel stalker, patriarchy-affirming, vulnerable and middle-class aspiring youth, and a lover forever. He could have been the Paul Newman of Hindi cinema but mainstream Hindi cinema believes that only fun should be taken seriously.

This book is lucid, comprehensive, and interesting. The language is terse and plain whereas arguments and statistics are self-explanatory in nature. More than that, academicians and budding scholars must engage with it because the way this book deals with the subtleties and nuances of feminism and women’s participation in the Indian labour-market, is absolutely a noble and original method. It explores and explains the life of working and employed women through the lens of a fangirling approach. Fangirls, in the present volume, are characterized as those persons who have agency and seek to be loved and respected the way Shah Rukh treats his female protagonists. Nothing less than that is accepted. Fangirls are in constant search for their Shah Rukh throughout the book and while some find him and live happily, others are not so lucky and their search goes on. Juxtaposing personal life with the professional journey of these fangirls, the present volume attempts to present the everyday battles of young Indian women in the changing socio-economic scenario.

Shrayana Bhattacharya tells us two stories about India’s lonely young women: their survival in professional space and their struggle in personal life. There are many women in her stories about love and work in India. Some of them are Vidya, Manju, Gold, accountant-fan woman, Zahira, and herself too. These women struggle to keep pace with changing times in Indian society. The stories about their experiences in the professional space bring out the best in the author. She gives an impactful impression with statistical presentation and social sciences concepts such as demographic anomaly, time-poverty, statistical straightjacket, spheres, markers of culture and liberalization. She excellently discusses the changing relationship between culture and wage gaps in reference to Indian women and families by bringing into play the rich explanations of income effect, education effect, underestimation effect, and the structural transformation of the economy. The gem of this work is the statistical presentation of women’s participation in the Indian workforce. The appendix is sharp and well-curated to substantiate the arguments and locate the status of women in Indian society. The author is in total grip when she is dealing with the economic aspects of changing Indian society with reference to working women. Moreover, being a woman of Delhi’s academic and cultural space, the author profoundly shows us the shallowness and fakeness of cultural-elites of the city. The male lovers, in all the stories including hers as well as in this book, seem to be frozen in time and space, who do not, and neither do they wish to understand the aspirations and sensibilities of modern Indian women. The author has marvellously depicted the picture of structures of patriarchy in Indian society. Moreover, she is well aware of her own self as well as the location of other participants in the broader socio-cultural and economic milieu of contemporary Indian society. The author seeks to understand if things have changed in any meaningful way for the female sex in India. How has the status of women progressed since 1974 when Vina Mazumdar, as a member of the Committee on the Status of Women in India, submitted the first official government report titled Towards Equality on the status of women in the country? She interviews Abhijit Banerjee, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Nivedita Menon, and Jean Dreze and comes to the conclusion that there is still a lot to be done. She enlists their inputs in her book, where Jean Dreze states that “there has been some positive change in gender relations in India during the last few decades, but it has been very slow”, whereas, for Mehta, the Indian state’s handling of women and gender issues had been a ‘catastrophic failure’.

The World Economic Forum 2020 report states that “the economic gender gap runs particularly deep in India….only one-quarter of women engage actively in the labour market (i.e., working or looking for work) – one of the lowest participation rates in the world and through some specific chapters, Lost in Liberalization, A Tale of Two Televisions, and An Equilibrium of Silly Expectations and Loveria, the author lets readers understand that how Indian women work, how they see it, what their notions and understandings of professional aspects of their work are (such as wages, mobility, professional aspirations). She also focuses on their personal issues like love, life, intimacy, romance, loneliness, dignity, and bargaining power within the patriarchal family structure.

On the larger canvas of story-telling of Indian women with reference to the class, caste, gender, region and religion, in a multicultural, multiethnic, and multilingual country like India, the caricature of Shah Rukh plays an extended cameo. He appears and disappears throughout the work, but sometimes, readers are left wanting more. In fact, his disappeared appearance is more profound and impactful than appearance during the stories of lovelorn fangirls. Hence, the author leaves scope and space for subtleties of social life to play their role throughout the book. Sometimes it may be felt that the fangirling has been overstretched to the extent that it looks more fictional than the lived-experience of India’s lonely young women.

The book, meandering between hard facts and romantic fiction, contains fourteen chapters. Each chapter brings a story of lonely or lovelorn young Indian women. The selection of stories is based on the author’s personal encounter with various characters in the book. The chosen method for the selection of participants was purposive and an ‘avalanche of snowballing’. As a scholar of economics, it is not hard for the author to see that it brings a kind of monotony to the book. The author must understand that Shah Rukh is a cultural phenomenon and it is not restricted to a certain heterosexual gendered person. There are many other gender persons who love Shah Rukh, and they have been ruined by the depiction of love on the silver-screen by Shah Rukh. It can be men as well. It would have been very interesting to have some narratives from a varied group of gender participants as well. The limitation of homogeneity in participants is apparent throughout the work and it results in a certain kind of dreariness. But here, it is also important to note that it was the author’s purpose to focus on India’s ‘lonely young women’ and their search for intimacy and independence, and to that extent, she purposefully conveys her research and thoughts through well-prepared narratives and stories.

The author attempts to weave stories in the light of the changing economic scenario in India. It can be safely said that she is brilliant while dealing with socio-cultural and economic realities engendered from paradigmatic economic policy shifts in India, but here and there, Shah Rukh emerges which breaks the rhythm and momentum of the socio-economic history of participants. Shah Rukh does not seem as purposeful as the author is in this book. Sometimes, he comes across as an item song in the reading of the book, which not many people prefer to witness during the narration of a lovelorn woman. The stories of India’s lonely young women are interesting but it is also apparent that the author is not a novelist. Her attempt is to present the multifaceted relationship of social realities in contemporary Indian society. Her economic analysis is riveting but the fictional parts are not as appealing. Therefore, it is difficult to categorize this book. The author may argue that it is not meant to be categorized, but with this argument, one reduces the scope for a wide readership on a specialized topic.

It is a long and well researched work with more than fifteen years of research having gone in by the author. In fact, the book is a collection of stories she put together during her personal and professional journey. The essential material for the book has been an understanding of the fangirl and their socio-economic journey. This is in the backdrop of seeking and being in love like the way Shah Rukh Khan does on screen – one that is always in the making, and evidently, we find rich narratives of lonely young women and their search for intimacy and independence in the present form of the book. Apart from that, the present volume has a potential to be seen as a work which has successfully depicted the effect of a cultural icon and mainstream Hindi cinema on the life of India’s young women in changing economic times. These young women are in the consistent search for recognition, love, and respect in their personal and professional life and here Shah Rukh and his films serve as an ideal type. In this sense, the present volume plays a significant role in collecting and sharing the stories and narratives of lonely young women and their aspirations in both their personal and professional life. These stories stand testament to the fact that cinema has a transcendental effect on diverse sections of society. These effects are shaping the lives of young people and when it comes to defining their social and personal lives, Shah Rukh paves the way. In this pursuit, the present book by Shrayana Bhattacharya can play the role of a guidebook.

Dr Bishnu Mishra is a Project Consultant at National Institute of Educational Planning & Administration.

He can be reached at bpmbhu@gmail.com

©TheDaak2023

Leave a comment