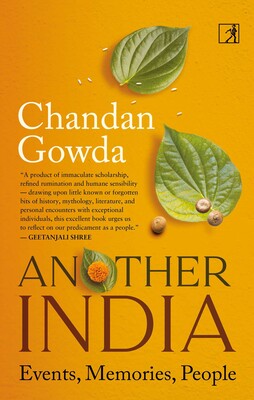

Another India: Events, Memories, People by Chandan Gowda, Simon & Schuster 2023, 267 pages, Hardback, ISBN: 9789392099748, ₹599.

By Soni Wadhwa

In India, like elsewhere, texts of cultural heritage, such as the epics, are touted as a means to rediscover one’s own identity and wearing it on one’s sleeve. The resistance to this narrative of timelessness, benevolence and relevance of these texts to contemporary time and space often comes in the form of a backlash. The sources of this heritage are touted as patriarchal, even misogynist, and casteist or coercive. The two positions – let’s say that of the fundamentalist and the liberal – find a refreshing revisit in Chandan Gowda’s recent book Another India. It is a collection of his columns that reflect on instances and episodes, anecdotes and folk tales, historical figures and community cultures, all woven together with a concern for the richness of everyday examples primarily from Kannadiga contexts. Each piece has a story, a folk tale, a historical event, or a historical figure that makes the larger point about community cultures in India, urging readers to go beyond the binary of liberal/illiberal in Indian thought and life, and to become listeners and readers of Indian tradition who understand the possibilities of ambiguities that exist among sources of Indian tradition.

The book has about 74 essays. Two examples will help point at the diversity of the material and also illustrate the approach and insight Gowda brings. The first essay, A People Without a Stereotype starts by pointing towards the absence of Kannadigas in ‘this cute visual scheme of federal unity’ as seen visible in images of brides and grooms on the walls of restrooms in the New Delhi airport and also in the way Kannadiga identity is somehow managed with a couple dressed in Coorg attire – that’s somewhat odd given that Coorg and Kannadiga identities are not one and the same thing – in Indian broadcast channel Doordarshan’s song from the 1980s, Mile Sur Mera Tumhara (p. 3), Gowda’s observation is:

The non-arrival of a generic Kannada identity is also a triumph of its heterogenous nature. None of Karnataka’s chief cultural zones, that is, the old Mysore region, coastal Karnataka, Coorg, Mumbai-Karnataka, and Hyderabad-Karnataka, has been able to stand in for the Kannada community image. Amidst the unpredictable twists in a fast-transforming India, a Kannadiga stereotype might yet emerge. At the moment, however, being an amorphous presence in the national imagination should mean a delicious freedom (p.5).

What starts as a narrative of absence turns into something of an occasion for celebration: instead of some hue and cry about absence of a community or identity, one finds ‘a delicious freedom’. That is the lens of engaging with identity, outside that of critique, that one must learn.

The second example is “The Adventures of Puttakka”, a folk tale narrating the story of Puttakka, a beautiful wife who cuckolds her husband with the village headman who lusts after her. The focus of the story is not what happens to her marriage after that, but Puttakka’s smart ways of confounding thieves who break into her house by seducing one of them and teaching him a lesson by biting his tongue. Gowda’s point behind drawing attention to this strange story of an unusual heroine, in contrast with the wronged Sita is:

The complex amoral story admires the quick-witted heroine while staying non-judgmental about her actions throughout. Besides, the husband’s overlooking of her affair with the headman contrasts with the more commonly found sentiments of injured male pride on such occasions (p.110-111).

The choice of story helps one realise that there is a lot more than epics to understand gender dynamics in the subcontinent of a different time. Methodologically speaking ‘anotherness’ seems to be Gowda’s take on the philosophical ‘Other’ that Western thought in general has been concerned with by evoking a sense of alternative narratives to the mainstream ones. These examples are an illustration of that ‘anotherness’ and are likely to be found charming by those interested in the nature of archives and memory. Gowda’s curation of ‘events, memories, people’ as conveyed in the title of the book stands out for the assortment of life experiences that need to become a part of debates and dialogues in the country. The book is also a rich example of how to archive, curate, and read different texts empathetically. One learns that critique is not noise, and that religion and rationalism are not antithetical to each other. Critique is also a way of engagement that could best be explained with the Buddhist idea of maitri. How to practice maitri within critique is an art towards the vision of ‘political creativity in the present’ ( p.124). This creativity uses ‘the mythological inheritance of India’ to work with “the cultural psychology of Indians” (p.134). It ‘melt(s)’ the epics and slightly upgrades them to the current times (p.145). There are quite a few metaphors to understand the practice of ‘anotherness’: ‘We need to acquire cultural sight by grafting on to the mother-creeper of the community min ( p.147).

Perhaps, a better title for the book is ‘Another India: Notes from Kannadiga Contexts’, for its anchoring in the region, the language. It is also an inspiration for one to speak courageously from one’s own linguistic or regional context without worrying about it being too particular, or risky when it comes to saying anything definite about a nation as heterogeneous as India. The particularity of the context might as well multiply with one’s own linguistic and regional context and inspire more versions of anotherness.

Soni Wadhwa teaches English at SRM University, Andhra Pradesh. Her research interests include digital archiving, pedagogy, spatiality and Sindhi Studies. Her digital archive PG Sindhi Library is dedicated to post Partition Sindhi writing in India. She is a regular contributor to Asian Review of Books.

Leave a comment